They will never be silenced

Remembering Javier Valdez on his third death anniversary

Posted on 15 May 2020

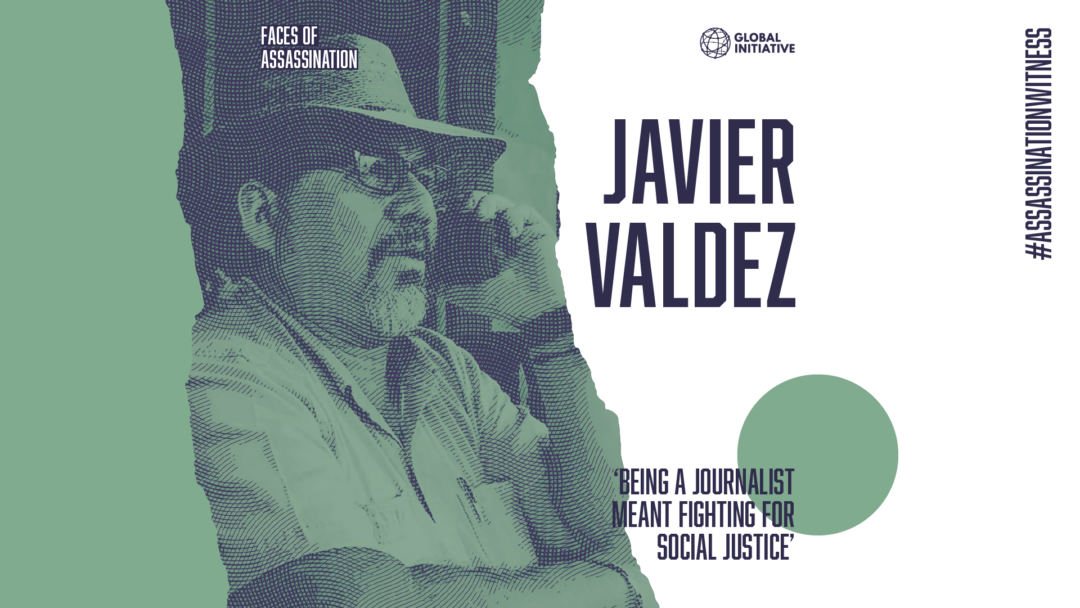

On the third anniversary of the death of assassinated Mexican journalist Javier Valdez we reflect on how resilience and collective memory can help assuage the pain of communities afflicted by organized crime.

On the third anniversary of the death of assassinated Mexican journalist Javier Valdez we reflect on how resilience and collective memory can help assuage the pain of communities afflicted by organized crime.

It has been three years since Javier Valdez Cárdenas was murdered outside the office of his newspaper in Culiacán, Sinaloa. Despite the time that has passed since that day, I still don’t know how to write about him. Endless pages have been dedicated to his work, his legacy – and his murder case, which has still not been concluded to this day. His is a story that has been told many times, and rightly so – by the time he died, he had become a celebrity of Mexican journalism. But it is also a story that needs to be told because, as I would find out, memory is a tool that can help heal a community’s pain.

I first met Javier in Culiacán, our home town, in 2016, by which time he was already renowned for his work. I had followed his work for years, but had not had any reason to meet him. However, when I began documenting community resilience against organized crime, as part of the #GIResilience project, he was the first person I contacted.

Our first conversation proved auspicious. ‘You want to know about resilience? Go talk to “the searchers”,’ he said. Javier put me in contact with Mirna Medina, a woman who was leading a collective of mothers looking for missing people in northern Sinaloa. The name of the group is Las Buscadoras (literally, the searchers). They have taken it upon themselves to look for people who have gone missing – in an area where abductions carried out by organized-crime groups and corrupt police members are all too common.

I went to Los Mochis, where I met Mirna and her group. A dozen women equipped with shovels and metal sticks welcomed me lovingly as Javier’s envoy. I accompanied them on one of their searches by the cornfields just outside the city. That day, these women uncovered human remains buried next to a ditch. It was a deeply sobering lesson on resilience in action, and I owe the experience to Javier.

I continued to stay in contact with him. He was a warm and approachable person; it felt like I’d known him for years within a short time. He had a way of making you feel acknowledged and heard. This is what made his journalism so special, and why he was so prolifically read. He wrote a weekly column in Riodoce, the newspaper he co-founded, that told the stories of the common folk in Sinaloa. Men and women would confide in him and share their personal experiences, which were often disheartening and even tragic. Javier would transform them into captivating stories that poignantly reflected the lives of ordinary people, and their lost ones, in the midst of the state’s war on drugs. He won several prestigious awards for his courageous work with Riodoce, investigating government corruption and drug-trafficking organizations (including, in 2011, the International Press Freedom Award of the Committee to Protect Journalists). He also won the love and respect of his community for his generosity and for his solidarity with the victims of injustice. And there are many of them in Sinaloa.

Following our conversations on resilience, we agreed that something more had to be done, not only to protect journalists, but also to raise awareness among the people in Sinaloa about how journalism can help make them resilient against crime. This was how the idea of the first Resilience Dialogues was born. Javier agreed to participate in these dialogues and host a media panel discussion. Just a couple of months before the first dialogues, he was shot in broad daylight. It seemed unthinkable to go ahead without his support, but we did. We used the platform to honour his memory, and that was another lesson on resilience in action too.

Three years later, our project has grown and transformed into the Resilience Fund. For me, Javier Valdez is still very much a part of this initiative. His partner, Griselda Triana, joined us in 2019 at the launch of the Fund. Griselda has become an activist in her own right, a voice for the families of murdered journalists. In Javier’s memory, she started a project supported by the Resilience Fund to document cases of assassinated journalists – Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries in the world for investigative journalists – and identify what makes their families resilient. High-level authorities in the Mexican government have recognized Griselda’s work. Her research has compelled them to pay more attention to the cases of murdered and disappeared journalists, providing reparations to their families.

Griselda Triana speaks at the Resilience Fund launch event in Vienna (May 2019)

In the three years since Javier Valdez was killed, more than 15 journalists have been assassinated in Mexico. These are murders that seek to terrorize and muzzle entire communities. So, as Javier did through his work, and Griselda is doing today, we must continue talking about these assassinations. The criminals and the corrupt authorities responsible for them want us to forget, to remain silent. But when a community bears witness to violence and remembers the lives and losses of their journalists, those communities may become more resilient against organized crime.

Our collective memory and our voices are our tool for justice. We won’t be silenced for Javier, or for any assassinated journalist.

Like Javier Valdez, many activists, human-rights defenders, lawyers, law-enforcement personnel and others have been assassinated because they have faced up to organized crime.