21 April 2018

Johannesburg, South Africa

Gezahegn Gebremeskel

Profession

Community

Motive

Political dissent

Adolfo Olivas

Ahmed Divela

Amit Jethwa

Artan Cuku

Babita Deokaran

Bayo Ohu

Berta Cáceres

Bhupendra Veera

Bill Kayong

Boris Nemtsov

Boško Buha

Chai Boonthonglek

Charl Kinnear

Chut Wutty

Chynybek Aliev

Cihan Hayirsevener

Daphne Caruana Galizia

Darío Fernández

Derk Wiersum

Deyda Hydara

Édgar Quintero

Edmore Ndou

Edwin Dagua

Federico Del Prete

Fernando Villavicencio

Gezahegn Gebremeskel

Gilles Cistac

Habibur Mondal

Igor Alexandrov

Jacob Juma

Ján Kuciak

Javier Valdez

Joannah Stutchbury

José Ángel Flores

Jules Koum Koum

Kem Ley

Luis Marroquín

Mahamudo Amurane

Marcelo Rivera

María Elena Ferral Hernández

Marielle Franco

Milan Pantić

Milan Vukelić

Muhammad Khan

Nelson García

Nihal Perera

Oliver Ivanović

Orel Sambrano

Perween Rahman

Peter R. de Vries

Rajendra Singh

Salim Kancil

Sandeep Sharma

Sikhosiphi Radebe

Slaviša Krunić

Soe Moe Tun

Victor Mabunda

Virgil Săhleanu

Wayne Lotter

Yuniol Ramírez

Zezico Guajajara

21 April 2018

Johannesburg, South Africa

Profession

Community

Motive

Political dissent

The locals called him George. Even some members of the small gangs of downtown Johannesburg would say ‘howzit, George’ when they saw him sitting on his regular bench on the corner of Kerk and Polly streets, chatting to people. Street kids would come up to him and say: ‘We don’t have money to buy food’, and he’d hand them something to eat. And if you had been robbed, and you lived or worked in the area, then you’d be sure to tell George. He was known for being able to locate and return your belongings within 24 hours.

On 21 April 2018, at about 5 p.m., Gezahegn Gebremeskel (aka George) was killed by a single bullet, which left him slumped on his bench outside Yamampela Fast Foods with blood pouring from his neck. He was just 48 years old. Although he was carrying R15 000 (roughly US$1 000) in cash, this was left untouched by the gunman, whom witnesses described as a ‘young boy’ and ‘slim’. Gebremeskel’s body was quickly surrounded by a crowd of people, who waited for 40 minutes for the police to arrive; it was another two hours before the body was finally moved.

Gebremeskel was an Ethiopian activist and a leader for the Ethiopian diaspora community in South Africa. As an army sergeant during the Ethiopian civil war, 21-year-old Gebremeskel had found himself in danger when, in 1991, the military was dismantled and the country’s new transitional government began to target and assassinate former soldiers. He responded by rallying against the post-war government, but this only escalated the threats to his life. He fled first to Kenya but there the authorities were killing activists in that country, so in 1997 he moved to South Africa.

Gebremeskel was a man plagued by past regimes: he didn’t flee Ethiopia on account of his political views, he fled on account of his past. At the time of his assassination, Ethiopia’s ruling party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, which he had fought for most of his life, had changed radically. The prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, had instituted national reforms and freed captured journalists. Interestingly, those suspected of ordering the assassination of Gebremeskel were no longer in power; Gebremeskel wasn’t killed during the heat of the regime he hated but rather scalded by its embers. And herein lies the conundrum of the case.

The author met with Fana Derge, spokesperson for the Ethiopian Community Association in South Africa, in Rosebank, Johannesburg. Since Gebremeskel’s assassination, Derge hasn’t felt comfortable visiting the city; he now lives in Pretoria. Asked why Gebremeskel was killed after the previous administration had ceased, Derge said: ‘It is because of the information that he had. They knew that one day Gebremeskel would expose the things that he had been told. They believed he would do it when the time was right, when it could make a difference.’ The right time would certainly have been after Ethiopia’s transition to the new regime. If Gebremeskel had released any explosive information earlier, it would have simply bounced off the old regime. ‘You have to wait for the change,’ Derge said. ‘And now the change has come.’ The irony isn’t lost on either of us.

According to Derge, the previous Ethiopian government was involved in money laundering and smuggling; they had wanted to bring some of that money into South Africa. Evidence of this began to reach Gebremeskel, and his informants hoped that he would be able to use his influence to bring about change. Gebremeskel had let people know that he had received some top-secret information but had refused to disclose his sources or give away any detail that would endanger the recipients of the information. It was this consideration for the safety of others that saw him recognized as trustworthy among South Africa’s Ethiopian community.

Relaying the fear that has gripped the community since Gebremeskel’s murder, Tamiru Abebe, head of the Ethiopian community association in South Africa and a close friend of Gebremeskel’s, told South Africa’s Mail & Guardian’s Simon Allison in 2018: ‘This is no ordinary killing. This is absolutely an assassination. More than 100% the Ethiopian government is to blame.’ The Ethiopian embassy has, however, strongly denied these allegations.

Despite the suspicion surrounding Gebremeskel’s death, police officers from Johannesburg central police station assigned to the case uncovered nothing. Although it is standard practice to look to security-camera footage, particularly in the absence of clear witness testimony, journalist Heidi Swart told the author she was sure the cameras were not working. She had reported at the time for the Mail & Guardian that there was no footage available. ‘I’ve done some more research into the functionality of the Johannesburg camera system, and as far as I can see, it’s a mess,’ she said. ‘So, I don’t think it’s a case of the metro police not wanting to release the footage of the shooting. I think it probably doesn’t exist.’

Taking action in the absence of police success, Derge’s organization paid R200 000 to private investigators over the course of six months in an attempt to solve the death of their friend and comrade. But the investigators also turned up nothing. ‘This is my opinion: the reason they weren’t able to uncover a clue is because this information is protected by influential entities,’ said Derge. It is believed that whoever hired Gebremeskel’s assassin was someone from Ethiopian’s old regime, someone who was scared of what Gebremeskel knew and anticipated it being released.

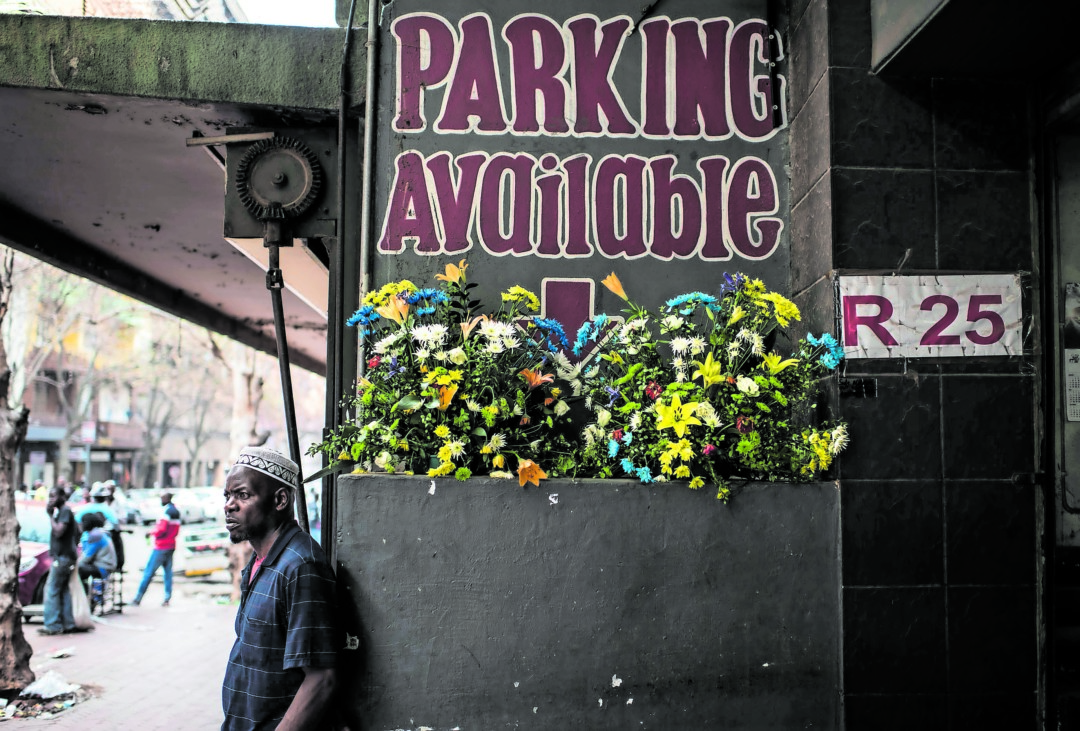

Flowers left by the community near where Gebremeskel died

‘Just before the day he was killed, there was a meeting between South Korean investors and South Africa-based Ethiopian businessmen at the Hellenic Cyprus club in Bedfordview,’ said Derge. ‘Gebremeskel, who didn’t like the idea of Ethiopia doing trade with Korea, allegedly caused a disturbance and was ejected from the club.’ While Derge believes that this had nothing directly to do with the assassination, it may highlight how an activist can be considered a problem because of the information he possesses.

When asked if anyone has replaced Gebremeskel as a central figure of activism in the Ethiopian community, Derge said no. ‘The political situation of our country is changing, so there isn’t much activism needed.’ But a sad pause accompanied the response. Derge, who was 22 when he left Ethiopia, has also given his life to politics and has spent much of that life fleeing the previous government. ‘I just ran away because it is better to be alive,’ he said.

The Ethiopian diaspora of downtown Johannesburg has, in Gebremeskel, lost its protector from the local gangs, the one person able to accommodate and link the two frequently antagonistic groups. ‘Where we work, we were never harassed and that has changed since he died,’ said Derge. Gebremeskel’s two surviving children now receive funds from the diaspora and will be able to visit Ethiopia safely one day should they wish to do so. Gebremeskel never once returned to Ethiopia in the 21 years that he lived in South Africa, but, as Derge revealed, finally doing so had been on the horizon: ‘Just before he died, he told me he had been in exile a long while and now was the time to go back home and live.’

16 January 2019

Accra, Ghana

Ahmed Divela

23 August 2021

Johannesburg, South Africa

Babita Deokaran

20 September 2009

Akowonjo, Lagos State, Nigeria

Bayo Ohu

18 September 2020

Cape Town, South Africa

Charl Kinnear

16 December 2004

Kanifing, Gambia

Deyda Hydara

22 April 2017

Beitbridge District, Zimbabwe

Edmore Ndou

3 March 2015

Maputo, Mozambique

Gilles Cistac

5 May 2016

Nairobi, Kenya

Jacob Juma

15 July 2021

Kiambu, Kenya

Joannah Stutchbury

4 November 2011

Yaoundé, Cameroon

Jules Koum Koum

4 October 2017

Nampula, Mozambique

Mahamudo Amurane

22 March 2016

Mbizana, Eastern Cape, South Africa

Sikhosiphi Radebe

10 January 2018

South Africa

Victor Mabunda

16 August 2017

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Wayne Lotter