16 December 2004

Kanifing, Gambia

Deyda Hydara

Profession

Media

Motive

Political dissent

Adolfo Olivas

Ahmed Divela

Amit Jethwa

Artan Cuku

Babita Deokaran

Bayo Ohu

Berta Cáceres

Bhupendra Veera

Bill Kayong

Boris Nemtsov

Boško Buha

Chai Boonthonglek

Charl Kinnear

Chut Wutty

Chynybek Aliev

Cihan Hayirsevener

Daphne Caruana Galizia

Darío Fernández

Derk Wiersum

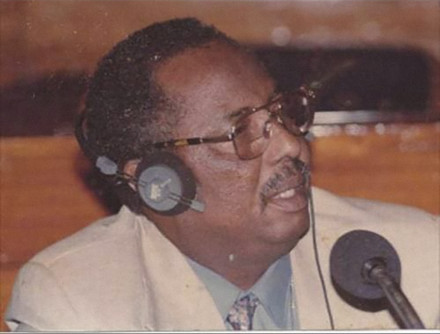

Deyda Hydara

Édgar Quintero

Edmore Ndou

Edwin Dagua

Federico Del Prete

Fernando Villavicencio

Gezahegn Gebremeskel

Gilles Cistac

Habibur Mondal

Igor Alexandrov

Jacob Juma

Ján Kuciak

Javier Valdez

Joannah Stutchbury

José Ángel Flores

Jules Koum Koum

Kem Ley

Luis Marroquín

Mahamudo Amurane

Marcelo Rivera

María Elena Ferral Hernández

Marielle Franco

Milan Pantić

Milan Vukelić

Muhammad Khan

Nelson García

Nihal Perera

Oliver Ivanović

Orel Sambrano

Perween Rahman

Peter R. de Vries

Rajendra Singh

Salim Kancil

Sandeep Sharma

Sikhosiphi Radebe

Slaviša Krunić

Soe Moe Tun

Victor Mabunda

Virgil Săhleanu

Wayne Lotter

Yuniol Ramírez

Zezico Guajajara

16 December 2004

Kanifing, Gambia

Profession

Media

Motive

Political dissent

It was 16 December 2004, and editor and journalist Deyda Hydara had just left his office in the Gambian capital of Banjul. He was on his way to celebrate the 13th anniversary of the independent newspaper The Point, which he had co-founded with his friend of 35 years, Pap Saine. The two had planned to meet at the ceremony of a wedding they had both been invited to. But Hydara never arrived, and when Saine tried to call him, his phone was turned off. Later, Saine received a call informing him that the friend he’d had since childhood had been shot and killed.

Born on 9 June 1946, Hydara was one of Gambia’s most distinguished journalists. He had worked as a reporter in Senegal and as a correspondent for the French news agency AFP’s Office in Dakar, Senegal for 33 years before his murder. But it was his more subversive work at The Point that is likely to have gained him his most powerful adversaries. He was a thorn in the side of the government at the time, led by former president Yahya Jammeh, who has been in exile in Equatorial Guinea since January 2017.

Saine and Hydara had grown up together, entered journalism together and in 1991 had gone on to create The Point together. Saine, who continues to run the newspaper along with Hydara’s son, says that the late journalist had always wanted to be the voice of the voiceless. Hydara had felt the need to educate and inform the people of Gambia, which he did most notably through his subversive column ‘Good Morning Mr President’. The column was addressed directly to President Jammeh, who had seized power in a coup in 1994. Jammeh was not a fan.

Yahya Jammeh’s 22-year rule was marked by widespread abuses against critics and political opponents, which included forced disappearances, extrajudicial killings and arbitrary detention. But it was the media that Jammeh and his government were the most averse to, as Saine explained from his home in Banjul. ‘They were watching us, monitoring us. They were not press-friendly; whatever we did that time they would take note. During Jammeh’s time, they were on the [case of] journalists who ran away; some journalists were killed; some were tortured. They did everything possible to discredit you,’ he said. ‘For 22 years, it was a nightmare for a journalist … there was self-censoring – you had to be careful what you say, what you write and everything, so there was self-censorship [and] there were the draconian laws.’

But despite the threats to his safety, Hydara had continued to fight against the country’s repressive government. He was notably outspoken on the issue of press freedom and was in the process of taking the government to court over the new anti-media laws it was trying to impose. It was just two days after the court hearing that Hydara was killed. According to Saine, he had received a number of threats: ‘He knew that they were after him. One day in the office he told the staff, “I am wearing bulletproof. I know these people are waiting for me and want to kill me any time”.’

Saine said that the combination of his column and the court challenge was the reason for Hydara’s murder, and that he, too, had reason to fear for his safety. As soon as Saine got the call to say that Hydara had been shot, he went straight to the hospital where Hydara’s body had been taken. Saine said that while he was at the hospital, government agents had warned him that he was also in danger. The next year, a high-ranking government official told him to stop the column, which he had continued in his friend’s honour; it was an order from Jammeh, declared Saine.

Hydara was a role model to many and a fierce proponent of press freedom, and his death left something of a vacuum in the Gambian media, Saine said. ‘Everybody was traumatized and surprised he was dead. A man helpful to international development killed like that. [His death] affected many young journalists or those who wanted to join the field to be journalists. After his demise, parents would not want their children to join the field,’ Saine revealed.

While Saine’s own friends and family asked him to stop working as a journalist, out of fear for his safety, others have encouraged him to carry on the fight: ‘Some friends convinced me and said to me that I must continue the struggle and the legacy of Deyda and press freedom in this country.’

Under Jammeh’s rule, Saine was arrested many times, including once in 2009 when he was jailed alongside members of the Gambia Press Union (GPU) for putting out a statement asking the government to speed up its investigations into Hydara’s death. The government claimed that the group had accused it of being behind the death. As a result, Saine and his fellow GPU members were sentenced to two years in prison, but fortunately they were let out after a month.

The place where Deyda Hydara was murdered, Banjul, Gambia

It wasn’t until Jammeh’s fall in 2017, after he lost the December 2016 election to Adama Barrow, that the ‘Good Morning Mr President’ column was reignited. The column is a legacy of Hydara’s that his family was keen to see continued, and is an important way of remembering all that the journalist had fought and died for. And, in recognition of Hydara’s sacrifice for press freedom, the front cover of every issue of The Point carries his portrait.

The GPU also celebrates and remembers Hydara every year. The union’s secretary-general, Saikou Jammeh (no relation of the former president), said there is no doubt as to who is responsible for Hydara’s death: ‘Jammeh was so bitter with people having a dissenting opinion, he wanted to suppress the press and suppress the citizens and the best way to do that was to curtail media freedoms. He attempted that but didn’t succeed. He found the person between him and that stupid goal was Deyda.’

Hydara’s family went to the Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States over his death. In 2014, the court found that the Gambian government had failed to meet its obligations by not conducting a thorough investigation of the journalist’s murder. The court also found there was a climate of impunity in the Gambia, ‘stifling freedom of expression’. Hydara’s family was awarded US$50 000 as compensation for the government’s failure to effectively investigate the death and a further US$10 000 to cover legal costs. So far, only half of the compensation has been paid out.

In 2017, arrest warrants were issued for the two suspects in Hydara’s murder – Sanna Manjang and Kawsu Camara. Both Manjang and Camara were former members of the armed forces, as well as members of the so-called Green Boys, a militia that carried out dirty jobs for Jammeh. However, both are now living outside the Gambia and therefore have not yet been arrested.

On 5 October 2018, the Gambian Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission was launched to look into alleged human-rights violations that had taken place during Jammeh’s rule. It began its hearings in January 2019. Supported by this new atmosphere of reconciliation, Pap Saine and Saikou Jammeh claim it is now a lot easier and safer to be a journalist in the Gambia. However, Hydara’s legacy and dedication to press freedom serves as a reminder of why the public need to support a free press and why the anti-media laws still on the books in the Gambia need to be opposed.

April 2022 update:

In April 2022, a German court ordered a trial against a Gambian citizen for allegedly participating in an army unit that carried out assassinations on behalf of former president Jammeh. He is charged with crimes against humanity and his alleged role in three murders, including Hydara’s.

November 2023 update:

In November 2023, a German court convicted Bai Lowe, the Gambian national, of crimes against humanity, murder and attempted murder under the principle of universal jurisdiction, which allows a country to prosecute crimes against humanity regardless of where they are committed. According to the court, Lowe was the driver in the paramilitary unit that is said to have killed opponents of former Gambian president Yahya Jammeh, including Deyda Hydara. Lowe was accused of helping to stop Hydara’s car and aiding the escape of one of the assassins. Human rights groups said the trial was an important step in the search for justice for Hydara.

16 January 2019

Accra, Ghana

Ahmed Divela

23 August 2021

Johannesburg, South Africa

Babita Deokaran

20 September 2009

Akowonjo, Lagos State, Nigeria

Bayo Ohu

18 September 2020

Cape Town, South Africa

Charl Kinnear

22 April 2017

Beitbridge District, Zimbabwe

Edmore Ndou

21 April 2018

Johannesburg, South Africa

Gezahegn Gebremeskel

3 March 2015

Maputo, Mozambique

Gilles Cistac

5 May 2016

Nairobi, Kenya

Jacob Juma

15 July 2021

Kiambu, Kenya

Joannah Stutchbury

4 November 2011

Yaoundé, Cameroon

Jules Koum Koum

4 October 2017

Nampula, Mozambique

Mahamudo Amurane

22 March 2016

Mbizana, Eastern Cape, South Africa

Sikhosiphi Radebe

10 January 2018

South Africa

Victor Mabunda

16 August 2017

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Wayne Lotter