3 March 2015

Maputo, Mozambique

Gilles Cistac

Profession

Criminal Justice

Motive

Political dissent

Adolfo Olivas

Ahmed Divela

Amit Jethwa

Artan Cuku

Babita Deokaran

Bayo Ohu

Berta Cáceres

Bhupendra Veera

Bill Kayong

Boris Nemtsov

Boško Buha

Chai Boonthonglek

Charl Kinnear

Chut Wutty

Chynybek Aliev

Cihan Hayirsevener

Daphne Caruana Galizia

Darío Fernández

Derk Wiersum

Deyda Hydara

Édgar Quintero

Edmore Ndou

Edwin Dagua

Federico Del Prete

Fernando Villavicencio

Gezahegn Gebremeskel

Gilles Cistac

Habibur Mondal

Igor Alexandrov

Jacob Juma

Ján Kuciak

Javier Valdez

Joannah Stutchbury

José Ángel Flores

Jules Koum Koum

Kem Ley

Luis Marroquín

Mahamudo Amurane

Marcelo Rivera

María Elena Ferral Hernández

Marielle Franco

Milan Pantić

Milan Vukelić

Muhammad Khan

Nelson García

Nihal Perera

Oliver Ivanović

Orel Sambrano

Perween Rahman

Peter R. de Vries

Rajendra Singh

Salim Kancil

Sandeep Sharma

Sikhosiphi Radebe

Slaviša Krunić

Soe Moe Tun

Victor Mabunda

Virgil Săhleanu

Wayne Lotter

Yuniol Ramírez

Zezico Guajajara

3 March 2015

Maputo, Mozambique

Profession

Criminal Justice

Motive

Political dissent

Gilles Cistac had tried to fix a country that couldn’t be fixed. These were the sentiments passed on by his daughter, Rosimele, on the occasion of her father’s birthday, two years after his death. Her message bore all the frustration and anguish typical of a child suddenly bereft of a parent and made to live in this world alone – especially when that parent has been taken in an act of stark and abject brutality. Rosimele Cistac was forced to watch as the light ebbed from her father’s eyes; he died in her arms.

On 3 March 2015, the prominent 53-year-old constitutional lawyer was shot outside a popular café in the centre of Maputo. According to witness accounts, he was getting into a taxi when four men approached in a car, lowered their windows and opened fire. The bullets that hit him went deep in his chest and abdomen, causing fatal injuries. Four hours later, he was declared dead at Maputo’s Central Hospital.

In the wake of Cistac’s murder, questions and suspicions started to arise. Although the attack occurred in broad daylight, the perpetrators have not yet been found. The investigation into the lawyer’s death bore little fruit, and the context in which he was killed cast a light on his friction with the ruling party, Frelimo.

As a lawyer specializing in the constitution, Cistac had seen the solution to a problem that had plagued Mozambique since the country’s transition from colonial power. He spoke openly of the need to decentralize the political power structure that has kept the country from realizing its potential as a true democracy. In a move that put him directly at odds with the party that has governed since 1975, Cistac proposed a way in which the opposition party, Renamo, could legally break away from the centralized government and establish autonomous regions. Under his plan, Renamo would govern the provinces of Sofala, Manica, Tete, Nampula, Zambezia and Niassa.

According to family and close friends, this proposal placed Cistac in the governing party’s firing line. Before his death, threats had been made to his life; and even though these were reported to local authorities, Cistac and his family were not offered any protection. In addition to the threats, a Facebook campaign had been created with the sole purpose of demonizing the lawyer, insulting him on the basis of his race and French origins, and even accusing him of being a spy. The campaign included a profile chillingly called ‘Calado Calachnikov’ (Portuguese for ‘Silencing with a Kalashnikov’), an answer to the unspoken question of how to deal with the perceived dissenter.

Pushback against Cistac’s views also came from Frelimo officials and members of pro-government media outlets. Frelimo spokesperson Damião José decried Cistac as an ‘ingrate’ who had disrespected the people of Mozambique.

To understand the circumstances in which Cistac was killed, one needs to understand the political context of Mozambique itself, João M Cabrita, author of Mozambique – The Tortuous Road to Democracy, said during an interview. After the country achieved independence, the constitution was designed to facilitate a multi-party democracy, but Mozambique ultimately became a one-party socialist state, dominated by Frelimo. Despite the fact that democratic elections came into effect in 1994, every subsequent election cycle has resulted in the same outcome: victory for Frelimo. Throughout Frelimo’s administration, several activists, journalists and lawyers who have directly challenged the ruling party have disappeared, been detained, killed or attacked.

‘In a nutshell: Frelimo believes the role it played to free Mozambique from the colonial yoke confers upon its leaders the right to treat the country as their dominion, where the fundamental principles of democracy are absent from the totalitarian project introduced at the dawn of independence and which essentially remains in place. Like others before him, Prof. Cistac was a spanner in the works,’ said Cabrita.

It is therefore no coincidence that Cistac’s stance on the decentralization of the state and criticism of the party’s strong influence on the judiciary rendered him a prime target. Cistac advocated impartiality within the judiciary, arguing that it was imperative that judges should be free of the influences of the political system. He argued that there should be structural reform, whereby some of the powers vested in the president would be curbed, namely regarding the appointment of magistrates.

Well-wishers lay a wreath in memory of Cistac

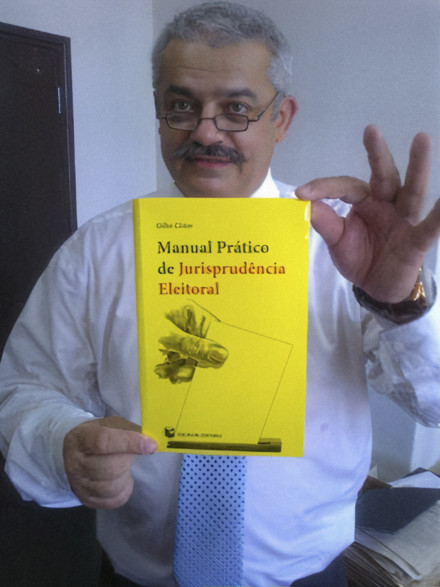

Gilles Cistac, who was a constitutional lawyer, holding the book he published on electoral law in Mozambique

The café in Maputo where Cistac was gunned down

In the midst of political machinations, Frelimo has utilized organized crime as a powerful weapon against dissent. Analysts have linked the party to instances of money laundering, human trafficking, and the smuggling of contraband, including drugs and ivory (associated with Frelimo patronage). Its methods for supressing opposition have included the deployment of ‘death squads’, widely believed to be the agents responsible for Cistac’s assassination and the deaths of several others, including Mozambican journalist Carlos Cardoso in 2000.

In essence, the state has been captured by organized crime. It festers under the protection of the political elite and is bolstered by endemic corruption, incompetence and greed in the highest echelons of power. Due to the staggering level of impunity that organized-crime groups enjoy under Frelimo, finding the perpetrators responsible for Cistac’s death could be almost impossible.

Cistac’s death not only reveals how deeply embedded organized crime is in Mozambique, it also demonstrates how frighteningly effective the government is at constraining the rights of the Mozambican people. According to Simphiwe Sidu, a lawyer belonging to the International Commission of Jurists’ Africa Regional Programme, ‘The killing of Cistac has definitely had an impact on the Constitutional right to freedom of speech of citizens of Mozambique in commenting on the current affairs of the country. It has increased a fear amongst human rights defenders in the country to freely speak on issues happening in the country.’

To many, Cistac was a man who wanted to change the system of the country in a way that held true to the spirit of the constitution formed in the wake of the country’s liberation. Such ambitions sadly cost him his life. His assassination is yet another reminder of the state’s willingness to dehumanize, maim and subjugate any who pose a threat to Frelimo’s continued political domination.

16 January 2019

Accra, Ghana

Ahmed Divela

23 August 2021

Johannesburg, South Africa

Babita Deokaran

20 September 2009

Akowonjo, Lagos State, Nigeria

Bayo Ohu

18 September 2020

Cape Town, South Africa

Charl Kinnear

16 December 2004

Kanifing, Gambia

Deyda Hydara

22 April 2017

Beitbridge District, Zimbabwe

Edmore Ndou

21 April 2018

Johannesburg, South Africa

Gezahegn Gebremeskel

5 May 2016

Nairobi, Kenya

Jacob Juma

15 July 2021

Kiambu, Kenya

Joannah Stutchbury

4 November 2011

Yaoundé, Cameroon

Jules Koum Koum

4 October 2017

Nampula, Mozambique

Mahamudo Amurane

22 March 2016

Mbizana, Eastern Cape, South Africa

Sikhosiphi Radebe

10 January 2018

South Africa

Victor Mabunda

16 August 2017

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Wayne Lotter