9 May 2018

San Luis Jilotepeque, Guatemala

Luis Marroquín

Profession

Community

Motive

Environmental and indigenous activism

Political dissent

Adolfo Olivas

Ahmed Divela

Amit Jethwa

Artan Cuku

Babita Deokaran

Bayo Ohu

Berta Cáceres

Bhupendra Veera

Bill Kayong

Boris Nemtsov

Boško Buha

Chai Boonthonglek

Charl Kinnear

Chut Wutty

Chynybek Aliev

Cihan Hayirsevener

Daphne Caruana Galizia

Darío Fernández

Derk Wiersum

Deyda Hydara

Édgar Quintero

Edmore Ndou

Edwin Dagua

Federico Del Prete

Fernando Villavicencio

Gezahegn Gebremeskel

Gilles Cistac

Habibur Mondal

Igor Alexandrov

Jacob Juma

Ján Kuciak

Javier Valdez

Joannah Stutchbury

José Ángel Flores

Jules Koum Koum

Kem Ley

Luis Marroquín

Mahamudo Amurane

Marcelo Rivera

María Elena Ferral Hernández

Marielle Franco

Milan Pantić

Milan Vukelić

Muhammad Khan

Nelson García

Nihal Perera

Oliver Ivanović

Orel Sambrano

Perween Rahman

Peter R. de Vries

Rajendra Singh

Salim Kancil

Sandeep Sharma

Sikhosiphi Radebe

Slaviša Krunić

Soe Moe Tun

Victor Mabunda

Virgil Săhleanu

Wayne Lotter

Yuniol Ramírez

Zezico Guajajara

9 May 2018

San Luis Jilotepeque, Guatemala

Profession

Community

Motive

Environmental and indigenous activism

Political dissent

On the morning of 9 May 2018, in the marigold-yellow central plaza of San Luis Jilotepeque, human-rights defender and community organizer Luis Arturo Marroquín stepped off a bus and entered a small store. He was scheduled to facilitate a workshop on civic responsibility that morning but, first, he needed to make some photocopies.

A few moments after he entered the store, two men emerged from a black Toyota Hilux and shot him nine times. It was approximately 9 a.m.

Marroquín was an indigenous Maya Q’eqchi activist on the national board of the Campesino Development Committee (CODECA in Spanish), a grassroots organization that fights for indigenous rights in education, health, energy and land. Marroquín had worked with CODECA for half a decade. As the coordinator for eastern Guatemala, he played a pivotal role in growing the organization’s regional presence.

On the same day, some 85 miles away – in the capital, Guatemala City – the organization was formally filing paperwork to launch its own political party, the Movement for People’s Freedom (MLP in Spanish). The new party aimed to move from protesting policy to shaping it in elected office. The party’s ultimate goal is to call a constitutional assembly and re-found Guatemala as a truly plurinational country.

It was too early for Marroquín to announce his own intentions for the 2019 elections but, according to his family, he had planned to run for office. And it would not have been the first time: he had run for mayor of his local village, San Pedro Pinula, in 2015. Marroquín didn’t win the election but served two terms on the village council.

Marroquín’s murder marked the start of a gruesome month for Guatemalan rights defenders. Seven indigenous activists were killed within days of one another. They were all affiliated with CODECA or a similar organization, the Campesino Committee of the Highlands (CCDA in Spanish). The first set of killings, starting with Marroquín, saw three activists shot dead around the country. Three weeks later, four more were killed by machete or knife attacks.

CODECA and the CCDA have both been outspoken defenders of indigenous and land rights. They educate members on legal rights, oppose harmful extractive industries and multinationals, and demand the resignation of corrupt officials – including, successfully, that of former president Otto Pérez Molina in 2015.

In recent years, both groups have shifted their tactics in a bid to transform the political system from within. The CCDA backed candidates in the 2015 election, and CODECA registered for the 2019 cycle. This presented a new threat to the establishment.

A week before Marroquín’s assassination, President Jimmy Morales – who is also being investigated for corruption – publicly lashed out against CODECA. After Marroquín’s death, the organization said in a press statement that it ‘publicly holds President Jimmy Morales responsible’.

Guatemala has long been a dangerous place for human-rights defenders. The Guatemalan Human Rights Defenders Protection Unit (UDEFEGUA in Spanish) has been tracking violence in the country. According to the unit, a defender has been killed about once a month since 2000 – and that number has been increasing. In 2015, 11 human-rights defenders were killed; 10 in 2016; 52 in 2017; and, in 2018, seven in one month

CODECA has been particularly hard hit. Neftalí López Miranda, one of the organization’s national leaders and the MLP’s candidate for vice president, said they have lost 38 members since the movement was founded. CODECA started on a sugar plantation in 1992, when 17 labourers banded together to protest against low pay, explained López. The group organized a strike and succeeded in having their salaries increased from 1.5 quetzals to 3 quetzals a month. They began to expand, mobilizing for land and water rights. In 2003 and 2004, they fought exploitative electricity prices. Today, the organization has a presence in 180 mostly rural communities around Guatemala.

In the area of Jalapa, Marroquín’s main focus was electricity. In an interview with the local magazine, EntreMundos, Marroquín explained: ‘There are a lot of rural people who have two, three lightbulbs. They don’t have a fridge or sound system or TV, and yet they’re paying Q200-250 per month. These are people who live on their crops. They don’t make any money.’ Many residents began refusing to pay for subscriptions, and instead began to connect directly – and illegally – to the electricity grid.

Marroquín's widow holds up a poster of her ex-husband, a 'defender of human rights'

Marroquín's family one year after his murder

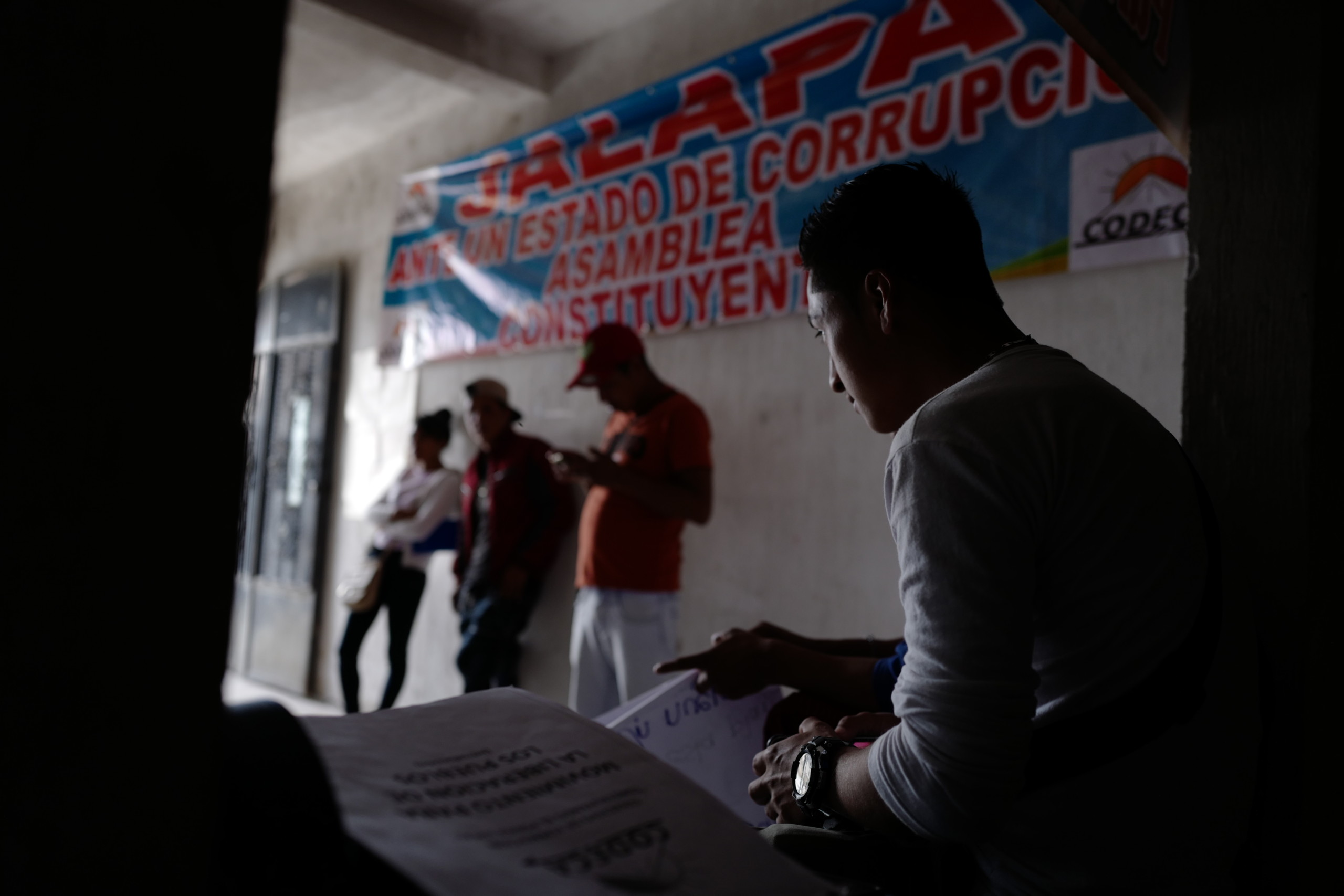

Young men supporting CODECA, the NGO Marroquín worked for

Nearly a year after Marroquín and his six fellow activists were assassinated, the killers remain at large. They have been described as ‘unknown assailants’. According to NACLA magazine, this suggests that the crimes were contract killings conducted by professional hitmen. These so-called sicarios (hired assassins) are believed to be connected to state forces and therefore act with impunity. In 2017, Iván Velásquez, head of the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala, found that 97 per cent of crimes in the country go unsolved.

Though no one has been arrested or charged for the murder, Marroquín’s family and former colleagues believe they know who might have been behind his death. His youngest son, Hector David, describes how his father had become a thorn in the side of local politicians – and especially the sitting mayor, José Manuel Méndez Alonzo – as well as the power distributor, Energuate.

Nery Rolando Agustín López, who worked closely with Marroquín since CODECA first established a presence in Jalapa nine years ago, now single-handedly takes on the duties that the two men had previously shared. An empty house in San Pedro Pinula serves as the headquarters both for CODECA and, now, the MLP. From here, Agustín López recalls how much has changed since he and ‘comrade Luis’ first began their work. ‘Everyone now has a voice and a vote. They have reclaimed their rights.’ From virtually zero, they built up a membership base of 6 000 members. That number is still growing.

Marroquín’s killers may still be at large, protected by a system that has always been stacked against the most vulnerable. But, for CODECA, that inequality only fuels their cause and commitment.

14 August 2005

Esteli, Nicaragua

Adolfo Olivas

2 March 2016

Honduras

Berta Cáceres

6 November 2011

Penonomé, Panama

Darío Fernández

15 May 2022

Santander de Quilichao, Colombia

Édgar Quintero

7 December 2018

Cauca, Colombia

Edwin Dagua

9 August 2023

Quito, Ecuador

Fernando Villavicencio

15 May 2017

Culiacán, Mexico

Javier Valdez

18 October 2016

Tocoa, Honduras

José Ángel Flores

9 July 2009

San Isidro, El Salvador

Marcelo Rivera

30 March 2020

Papantla, Veracruz, Mexico

María Elena Ferral Hernández

14 March 2018

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Marielle Franco

15 March 2016

Honduras

Nelson García

16 January 2009

Valencia, Venezuela

Orel Sambrano

13 October 2017

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Yuniol Ramírez

31 March 2020

Zutiwa, State of Maranhão, Brazil

Zezico Guajajara