26 September 2015

Selok Awar-Awar, East Java, Indonesia

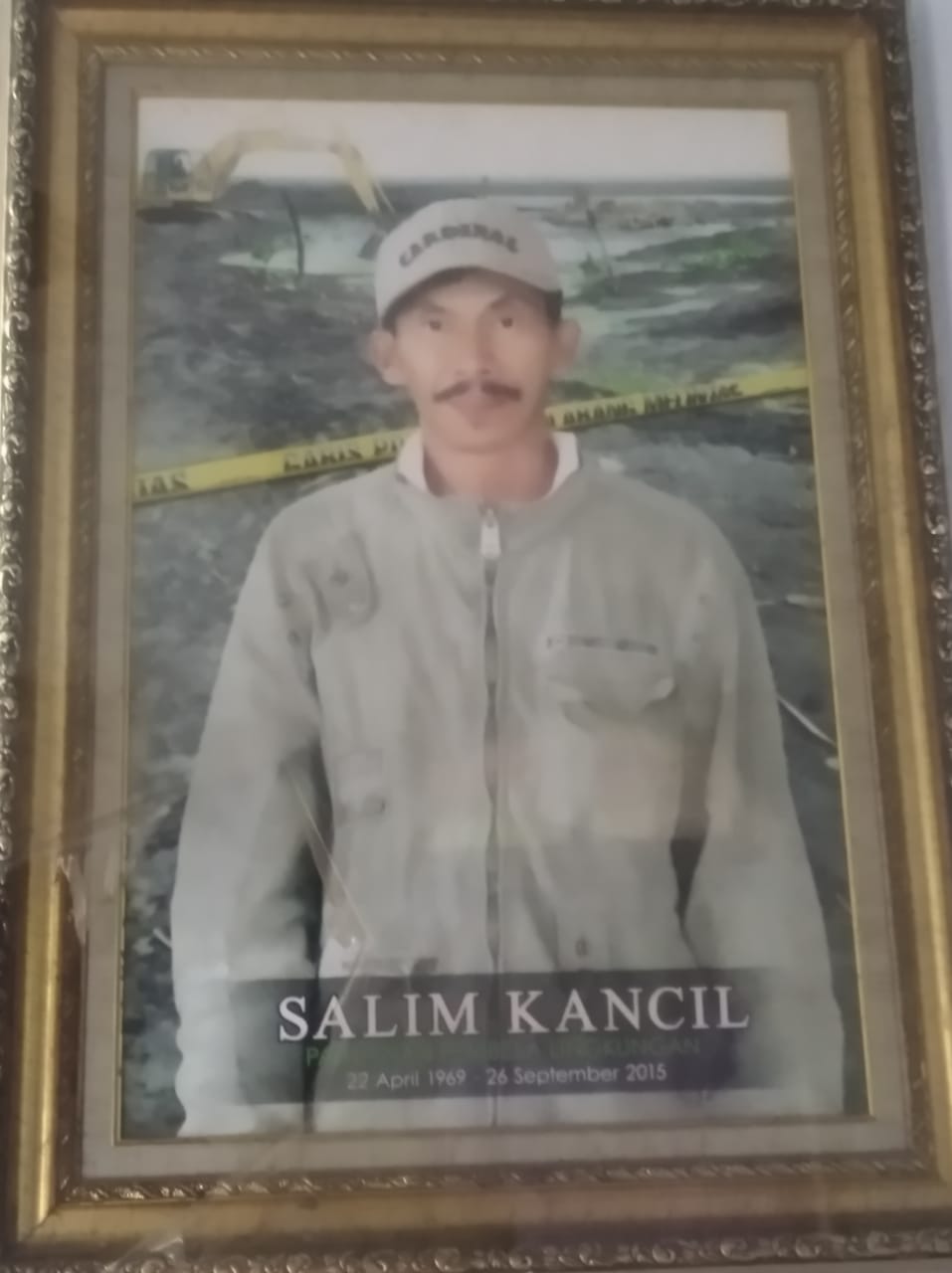

Salim Kancil

Profession

Community

Motive

Environmental and indigenous activism

Exposure of illegal activity

Adolfo Olivas

Ahmed Divela

Amit Jethwa

Artan Cuku

Babita Deokaran

Bayo Ohu

Berta Cáceres

Bhupendra Veera

Bill Kayong

Boris Nemtsov

Boško Buha

Chai Boonthonglek

Charl Kinnear

Chut Wutty

Chynybek Aliev

Cihan Hayirsevener

Daphne Caruana Galizia

Darío Fernández

Derk Wiersum

Deyda Hydara

Édgar Quintero

Edmore Ndou

Edwin Dagua

Federico Del Prete

Fernando Villavicencio

Gezahegn Gebremeskel

Gilles Cistac

Habibur Mondal

Igor Alexandrov

Jacob Juma

Ján Kuciak

Javier Valdez

Joannah Stutchbury

José Ángel Flores

Jules Koum Koum

Kem Ley

Luis Marroquín

Mahamudo Amurane

Marcelo Rivera

María Elena Ferral Hernández

Marielle Franco

Milan Pantić

Milan Vukelić

Muhammad Khan

Nelson García

Nihal Perera

Oliver Ivanović

Orel Sambrano

Perween Rahman

Peter R. de Vries

Rajendra Singh

Salim Kancil

Sandeep Sharma

Sikhosiphi Radebe

Slaviša Krunić

Soe Moe Tun

Victor Mabunda

Virgil Săhleanu

Wayne Lotter

Yuniol Ramírez

Zezico Guajajara

26 September 2015

Selok Awar-Awar, East Java, Indonesia

Profession

Community

Motive

Environmental and indigenous activism

Exposure of illegal activity

On 26 September 2015, a 52-year-old farmer became the first environmental activist to be murdered in the Indonesian province of East Java. Salim, often known by the nickname Kancil, was a vocal critic against sand mining in the village of Selok Awar-Awar, Lumajang regency, where he lived.

Salim was beaten in the village by a mob carrying sharp weapons, stones and logs. He was then tied with a rope and dragged for 2 kilometres to the village’s meeting hall, where he was further beaten and tortured. The mob then took Salim to a nearby cemetery, where they beat him to death.

Salim and other farmers had argued to the government that sand mining was creating large holes on the beach, causing seawater to flood their fields. Salim’s own field had been turned into a parking lot for mining trucks, without him having received any compensation. In response, Salim and other villagers had staged a rally on 9 September 2015 to protest the mining operations in Selok Awar-Awar. The next day, the villagers were threatened with death if they continued opposing the mine, but this did not deter them. On 25 September, Salim and the other villagers organized another protest the following day, with around 200 people estimated to gather. But before the rally could go ahead, Salim was murdered.

The police subsequently arrested the people who had attacked Salim. As many as 37 people were taken to court, including the two who orchestrated the murder: Haryono, who was serving as the chief of the Selok Awar-Awar at the time of the incident, and his colleague Mat Dasir. In addition to being charged with premeditated murder, Haryono was charged with illegal mining activities and money laundering. The court ordered Haryono to pay 2 billion rupiahs or IDR (US$140 000) in fines for both crimes. For planning Salim’s murder, Haryono and Dasir were sentenced to 20 years in prison in June 2016. Salim’s case also implicated at least three police officers, who were found guilty of accepting bribes from Haryono in exchange for their services guarding the entrance to the mining area.

Haryono had begun operating the illegal sand mine in June 2014 and had asked Dasir to help him run it. The mine generated a daily revenue of IDR40.5 million (US$2 800), IDR21.3 million (US$1 480) of which went straight into Hartono’s pocket. By comparison, farmers in Indonesia earn an average of IDR26 000 (US$2) per day, or less than 1 per cent of what Hartono was making from the illegal mine.

Rohim Ardy, a villager who became an environmental activist after Salim’s death, said the mob who beat Salim to death were thugs controlled by Haryono. ‘He had dozens of thugs,’ Rohim said. ‘He used to have 12 subordinates as members of his campaign team [for village election]. After he started the illegal mining operation, that team grew to dozens more.’

Salim’s death was the reason why Rohim, who used to be married to Salim’s niece, decided to join the movement against the mine, despite previously being reluctant. ‘Salim’s team had invited me to join the protest against the illegal mine in Lumajang coast,’ he said. ‘But I was not interested, so I didn’t join.’ Rohim was not the only one unwilling to oppose illegal sand mining at the time. According to him, many villagers were afraid of joining the protest movement because of the presence of thugs in the region. ‘Lumajang was controlled by mafia or thugs,’ he said. ‘So it was very normal for villagers to become apathetic to the movement.’

However, the presence of criminal activity in the area did not dissuade Salim. Despite the frequent intimidation by thugs, Salim went ahead with his fight, according to another activist, Abdullah Al Kudus (‘Aak’), who used to mentor Salim. ‘He was a brave man; that’s the thing that stood out the most about him,’ Aak said. ‘No matter how many trucks he had to block, he didn’t think of the risk. He kept on fighting.’

Aak remembers Salim as a man of few words, but a good listener. ‘Salim was a quiet man. He didn’t talk much, but he paid attention to other peoples’ words,’ Aak said. But something Salim did say left a mark on Aak. ‘One month before he died, Salim told me that if he had to die fighting for the environment, he would shake the whole of Indonesia. There was not an ounce of fear [in his eyes].’

It was Salim’s courage that moved many of the villagers, including Rohim, to take up the fight against illegal sand mining. ‘Salim was just a commoner who was brave enough to fight tyranny,’ Rohim said. ‘So after that, many people became aware of the problem. Many of us wanted to learn [how to fight against the illegal mine]. Many students took to the streets.’

The villagers’ movement pushed the head of the Lumajang regency to impose a ban on all mining activities without permits in the region. ‘But now, these illegal mines have started popping up again,’ said Rohim. As recently as 2022, locals of Bades, in the southern coastal part of Lumajang, spotted mining activities in their village, with sand trucks coming in and out. ‘Locals who saw the trucks were silent; they couldn’t comment or ban [the trucks from coming in],’ said a villager named Hamdi. The mines are allegedly illegal as the companies do not have complete permits.

Aak said that shortly after Salim’s death, the local government agreed to stop all kinds of mining activity in the southern coast of Lumajang and turned the area into a conservation area. However, the agreement seems to have been violated. ‘Why does the spatial plan in Lumajang still allow for mining activities even though it’s clear that this has violated the agreement [struck with the government] after Salim Kancil’s death in 2015,’ he said. ‘We reject all sand-quarrying activities in coastal areas. The government of Lumajang must show concrete actions, not just statements saying they reject mining activities.’

Even though there has yet to be decisive government action to protect the coastal environment of Lumajang, Salim’s death has flamed the spirit of the locals to fight back against sand mining. Many people in Lumajang regency now reportedly wear shirts bearing the message, ‘In our land, lives are not worth as much as mines.’ ‘Salim didn’t die for nothing,’ Aak said.

20 July 2010

Gandhinagar, India

Amit Jethwa

15 October 2016

Mumbai, India

Bhupendra Veera

21 June 2016

Sarawak, Malaysia

Bill Kayong

11 February 2015

Klong Sai Pattana, Thailand

Chai Boonthonglek

26 April 2012

Koh Kong, Cambodia

Chut Wutty

5 May 2004

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Chynybek Aliev

20 August 2000

Dhaka, Bangladesh

Habibur Mondal

10 July 2016

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Kem Ley

16 October 2018

Haripur, Pakistan

Muhammad Khan

5 July 2013

Deraniyagala, Sri Lanka

Nihal Perera

13 March 2013

Karachi, Pakistan

Perween Rahman

19 June 2018

India

Rajendra Singh

24 March 2018

Bhind, Madhya Pradesh, India

Sandeep Sharma

13 December 2016

Monywa, Myanmar

Soe Moe Tun