Far from ‘mission accomplished’ on the Caruana Galizia murder case

by Mark Micallef

Posted on 05 Mar 2021

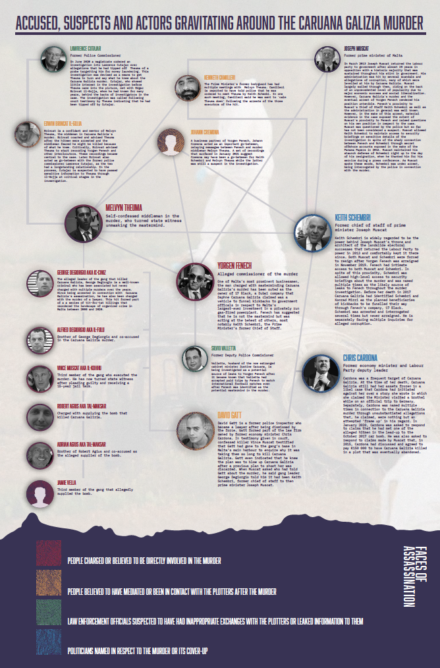

The investigation into the murder of Maltese anti-corruption journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia has been a violent rollercoaster since she was blown up in her car on 16 October 2017. Long periods of silence and inertia typically alternate with moments of rapid development. In February 2021, the case experienced such a moment of intensity, described as a potential milestone on the way to full justice by Caruana Galizia’s family. However, much more work needs to be done to fully uncover all players implicated in the assassination.

On 23 February, one of the three men charged with executing the hit, 58-year-old Vince Muscat, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 15 years in jail as part of a plea-bargain agreement. Simultaneously, the government announced that it had granted Muscat a presidential pardon in exchange for evidence in the murder of lawyer Carmel Chircop, who was gunned down in October 2015.

Muscat admitted that he had killed Chircop but claimed that he had been commissioned by brothers Robert and Adrian Agius and their associate Jamie Vella – known drug traffickers with connections to the Sicilian and Albanian underworld. Muscat also told the police, as part of his deal, that the Agius brothers and Vella had supplied the bomb that killed Caruana Galizia.

Muscat’s guilty plea undoubtedly consolidates the prosecution’s case against the accused, particularly the alleged co-executors of the hit, George and Alfred Degiorgio. It also finally puts in the dock Vella and the Agius brothers. It had long been known that the trio was allegedly involved in the Caruana Galizia murder and a spate of gangland murders that rocked Malta for over more than a decade. The level of impunity surrounding their alleged crimes was an especially glaring indictment of the weakness of Malta’s law enforcement and rule of law.

In fact, their arraignment was the culmination of a long, tortuous process. Muscat made it known to the police that he was willing to spill the beans on the Caruana Galizia murder and several other high-profile crimes as far back as May 2018. After having been debriefed, his testimony was initially dismissed by former police commissioner Lawrence Cutajar, who is himself currently under investigation for allegedly colluding with the murder’s middleman.

Cutajar’s successor, Angelo Gafa, an investigator with a ‘no-nonsense’ reputation, is said to have let Muscat’s lawyers know he was willing to consider the evidence more seriously. However, even after this second approach, there was a dangerously long lapse of time in which the suspects Muscat was willing to testify against could have taken actions to pervert justice, avoid arrest or worse.

Against this backdrop, the celebratory tone struck in press conferences given by the prime minister after these latest arraignments, stating that the progress was clear evidence that the ‘institutions were functioning’, appears misplaced. Combined with separate comments by the police commissioner, who said he believed ‘all the executors and masterminds’ in the case had been arrested, an implicit message of ‘mission accomplished’ was conveyed.

The implication is that little further progress should be expected on the murder case. This is in spite of an abundance of material evidence and testimony that has emerged over the past three years pointing to a conspiracy of politicians, government officials and law enforcement officers engaged in intimate dealings with the suspects in the murder and apparently colluding in its cover up.

Only a week after Prime Minister Robert Abela disingenuously stated that ‘no past or present politician had been found to be involved in the murder so far’, the police interrogated former economy minister and deputy leader of the Labour Party, Chris Cardona.

Just over a week after that, more details were revealed in Muscat’s testimony, his first extensive – and shocking – account of Caruana Galizia’s murder given in court. Muscat implicated both Cardona and Keith Schembri, the all-powerful chief of staff to former prime minister Joseph Muscat (no relation to Vince Muscat) in the attempt to help the perpetrators get away with the murder. Critically, in his testimony, Muscat alleged they may have had knowledge of the hit before it was executed.

Cardona had already been named multiple times in connection to the Caruana Galizia murder, most sensationally in a letter that claimed he commissioned it. The letter had been surreptitiously passed on to the alleged murder mastermind, Yorgen Fenech, while he was on police bail and appeared to coach him on what to tell the police.

Cardona vehemently denied any connection, dismissing the claims as an attempted ‘frame up’. However, under interrogation, following Vince Muscat’s latest revelations, Cardona was asked to respond to fresh claims that, in 2015, he had discussed and agreed to pay €150 000 to have Caruana Galizia killed in a plot that was eventually abandoned. He was also questioned about meetings with one of the alleged hitmen in the lead-up to and after the October 2017 car bombing.

Specifically, Muscat testified under oath that he had driven the Degiorgio brothers on multiple occasions to meet Cardona at the ministry’s office and the office of the prime minister, in the capital, Valletta, as well as at the Labour Party’s headquarters. Critically, he identified Cardona as one of the gang’s main sources of information on the investigation while the probe was taking place.

The killers had three weeks’ notice of the police raid in December 2017 in which they were eventually arrested. On the morning of the arrest, they gathered early in the morning at their main base – a quayside storage in Malta’s main port known as the ‘potato shed’ – and calmly waited for the police to arrive, because they were certain that at least two of them would walk away unscathed ‘with all the help they would get’.

Beyond Cardona, in the past two years a staggering amount of the material and circumstantial evidence, as well as multiple testimonies given in court and to the police, have also raised disturbing questions on the actions of Schembri. Former prime minister Muscat was forced to step down in disgrace in January 2020, shortly after the arrest of the alleged murder mastermind Yorgen Fenech – one of Malta’s most prominent businessmen intimately connected to Muscat and Schembri.

Since Caruana Galizia’s assassination, Fenech was exposed as the owner of 17 Black, a Dubai company that Caruana Galizia had revealed eight months before she was killed. The company is alleged to have been created as a vehicle to funnel kickbacks into offshore secret companies established by Schembri and former Energy Minister Konrad Mizzi shortly after they were elected to power in 2013 and which were exposed by Caruana Galizia and later in the Panama Papers.

Most of Caruana Galizia’s focus before she died zeroed in on the award of a contract for a €450 million gas power station to a group in which Fenech was a director and co-owner. The plant, Malta’s largest ever investment in the energy sector, was a central plank of the electoral programme that returned Joseph Muscat’s Labour Party to power with a historic majority – a victory largely credited to Schembri.

On the night before Yorgen Fenech was arrested on 19 November 2019, as he attempted to flee the country on board his yacht, he was on the phone with Schembri in an infamous 24-minute conversation. Joseph Muscat corroborated Schembri’s defence that he had called Fenech at Muscat’s request, in a bid to convince him not to leave Malta. However, when police officers arrested Schembri – well-known to be glued to his mobile device – he claimed to investigators that he had lost his phone.

At Fenech’s request, Schembri put murder middleman Melvyn Theuma on the state payroll in a phantom government job very shortly after the murder was commissioned. Schembri was also identified as the man who orchestrated to covertly send a letter to Fenech while he was on police bail, coaching him to blame the hit on Cardona. In the first session of his testimony in court, Vince Muscat provided more material, suggesting for the first time that Schembri may have had knowledge of the murder before it was executed.

Muscat testified that David Gatt, a sacked police inspector turned lawyer who has long been suspected of involvement with organized crime and was a partner in Cardona’s law firm, had visited the gang’s base prior to the murder to enquire why it was taking them so long to kill Caruana Galizia. Muscat testified that George Degiorgio told him that Gatt had been informed of the hit by Schembri.

This is on top of other testimonies and evidence indicating Schembri as the alleged source of highly confidential information passed on to Fenech and multiple middlemen associated with the case throughout the investigation.

Sources close to the investigation say one of the justifications used by the Malta Police Force for not moving against Schembri, Cardona and others in respect to this alleged attempt to cover up for Caruana Galizia’s murder is that Maltese law has weak provisions for association with a crime after the fact. This may well be the case and is a point that should stimulate legislative reforms that would bring Malta’s legal capability to fight high-level organized crime into the 21st century.

However, Schembri and other government officials, such as Kenneth Camilleri – the former prime minister’s bodyguard, who is said to have intermediated in discussions to bail the three hitmen shortly after being charged – are subject to provision of laws such as the Official Secrets Act. The act is designed to regulate the disclosure of confidential information by public officials. This is on top of existing provisions criminalizing obstruction of justice that would apply across the board, particularly to police officials suspected of collusion with the alleged perpetrators.

Caruana Galizia’s assassination has rocked Malta’s foundations. Her reportage on government corruption, right up to her last blog post, which she published minutes before being killed, connected virtually all of the political protagonists named directly or indirectly in her murder investigation.

Since her death, a shocking picture of corruption and collusion between Maltese politics, business and crime has emerged, to the point of making the vivid and damning picture she portrayed in her reporting pale in comparison. The country will only be able to chart a way forward from such a watershed moment when the full implications of Caruana Galizia’s assassination and reason for it are exposed in full. This is because understanding why Caruana Galizia was killed is intimately linked with revealing who was involved in the conspiracy to cover it up and why.