9 July 2009

San Isidro, El Salvador

Marcelo Rivera

Profession

Community

Motive

Environmental and indigenous activism

Political dissent

Adolfo Olivas

Ahmed Divela

Amit Jethwa

Artan Cuku

Babita Deokaran

Bayo Ohu

Berta Cáceres

Bhupendra Veera

Bill Kayong

Boris Nemtsov

Boško Buha

Chai Boonthonglek

Charl Kinnear

Chut Wutty

Chynybek Aliev

Cihan Hayirsevener

Daphne Caruana Galizia

Darío Fernández

Derk Wiersum

Deyda Hydara

Édgar Quintero

Edmore Ndou

Edwin Dagua

Federico Del Prete

Fernando Villavicencio

Gezahegn Gebremeskel

Gilles Cistac

Habibur Mondal

Igor Alexandrov

Jacob Juma

Ján Kuciak

Javier Valdez

Joannah Stutchbury

José Ángel Flores

Jules Koum Koum

Kem Ley

Luis Marroquín

Mahamudo Amurane

Marcelo Rivera

María Elena Ferral Hernández

Marielle Franco

Milan Pantić

Milan Vukelić

Muhammad Khan

Nelson García

Nihal Perera

Oliver Ivanović

Orel Sambrano

Perween Rahman

Peter R. de Vries

Rajendra Singh

Salim Kancil

Sandeep Sharma

Sikhosiphi Radebe

Slaviša Krunić

Soe Moe Tun

Victor Mabunda

Virgil Săhleanu

Wayne Lotter

Yuniol Ramírez

Zezico Guajajara

9 July 2009

San Isidro, El Salvador

Profession

Community

Motive

Environmental and indigenous activism

Political dissent

When he was a teenager, Miguel Ángel Rivera joined his older brother, Marcelo, to do community work in their home town of San Isidro in the department of Cabañas, El Salvador. In the early 1990s, they would collect donated books and take them to an abandoned building that had been used to store cadavers during the country’s civil war. This became San Isidro’s first library and cultural centre.

The Rivera brothers soon founded the Asociación San Isidro Cabañas (ASIC). Their organization has, as Miguel Ángel explained, an ‘umbilical connection’ to two other prominent community groups in the region – the Asociación de Desarrollo Económico Social de Santa Marta (ADES) and Radio Victoria.

Cabañas is a traditional stronghold of the Salvadoran military, with links to conservative politicians and businessmen. ‘There had been no protests here ever, not even during the war,’ said Miguel Ángel. Against this backdrop of terrified silence, the brothers began to raise their voices and those of the community.

Their work attracted a violent backlash when they launched a campaign to raise awareness about the potential dangers of gold mining. Pacific Rim, a Canadian mining corporation that was later sold to Australian company OceanaGold, had been granted permission to prospect for gold and silver in Cabañas. When they discovered deposits, the company solicited permission to build a mine. They also launched a public-relations campaign, promising that the mine would bring jobs and progress, and that the environment would remain healthy. The company tried to allay fears around two concerns in particular: its plans to strip gold from the rock using cyanide, and a decision to power the mine using the Lempa River, El Salvador’s main source of drinking water.

Cabañas community leaders went to neighbouring countries to visit opencast mines, similar to the one that Pacific Rim planned to develop. Miguel Ángel visited a mining site in Honduras. He remembers encountering a giant pile of rock that had been stripped with cyanide; there was an overpowering chemical smell and a school next door. The people who lived around the mine, he saw, were missing teeth and suffered from rashes on their skin.

The locals spoke to him about having lost their agricultural livelihoods when the mining affected the water table, and wells dried up. Miguel Ángel recorded these interviews and, on his return, ASIC showed the video to the communities of San Isidro. At the same time, Marcelo began speaking out on Radio Victoria and leading environmentalist marches.

In June 2005, people from the state partnered with community groups across the country and formed a central coordinating committee, the Mesa Nacional Frente a la Minería Metálica.

But as opposition grew to the proposed mine, Pacific Rim was making headway with El Salvador’s political elite. Miguel Ángel said the company had a firm strategy in place by 2007. He believes that while they were canvassing bureaucrats in the capital to expedite the licensing process, Pacific Rim also established mutually beneficial relationships with various mayors across Cabañas. Leveraging the mayors’ political networks, they would hire supporters to promote mining within communities. These moves by the mining firm exacerbated tensions. The list of parties who had a vested interest in Pacific Rim’s success was growing. Their most visible obstacle was Marcelo Rivera.

‘He was doing something that had never been done in San Isidro,’ said Oscar Beltrán, a journalist at Radio Victoria, explaining how Marcelo was challenging long-standing corruption and traditional power structures by ‘confronting them directly’. It did not go unnoticed – he barely survived a first murder attempt, when a truck with unidentified men tried to run him over. Yet he continued to serve as ‘the visible face of protest,’ Beltrán said.

In October 2005, a United States scientist named Dr Robert Moran released a scathing review of the company’s environmental impact exam. The Salvadoran state was divided over the issue when then Salvadoran Ombudswoman for the Environment, Yanira Cortez, voiced her concern about the viability of mining in El Salvador.

The protests in Cabañas were ‘a desperate cry in the face of the threat that these projects may represent to life,’ Cortez later stated in a deposition. She said that the state’s decision to continue entertaining Pacific Rim’s bid showed a ‘disregard for human beings in favour of private financial interests’. Pacific Rim’s progress in acquiring a concession then faltered and, in 2009, with pressure against the mining project mounting from civil-society groups and the media, the Salvadoran president announced that the government would not grant the company a mining concession. In an attempt to reverse this, Pacific Rim sued the government of El Salvador in April 2009 at the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) – a World Bank trade dispute settlement tribunal in Washington, DC.

Two months later, on 18 June, Marcelo Rivera was kidnapped. His body, which, according to the autopsy, showed signs of torture, was found about three weeks later at the bottom of a well in Cabañas.

The murder kicked off a wave of violence that lasted eight months, during which at least four anti-mining activists were murdered and many other people received death threats, including six journalists at Radio Victoria. Several people fled El Salvador, fearing for their lives. ‘Every time we heard a car outside, we thought, “Shit, they’re coming to get us”, ’ said Miguel Ángel.

Residents of Cabañas, El Salvador, at a celebration of El Salvador’s win in a World Bank tribunal over Canadian mining company Pacific Rim. They hold signs protesting against mineral mining, 4 November 2016

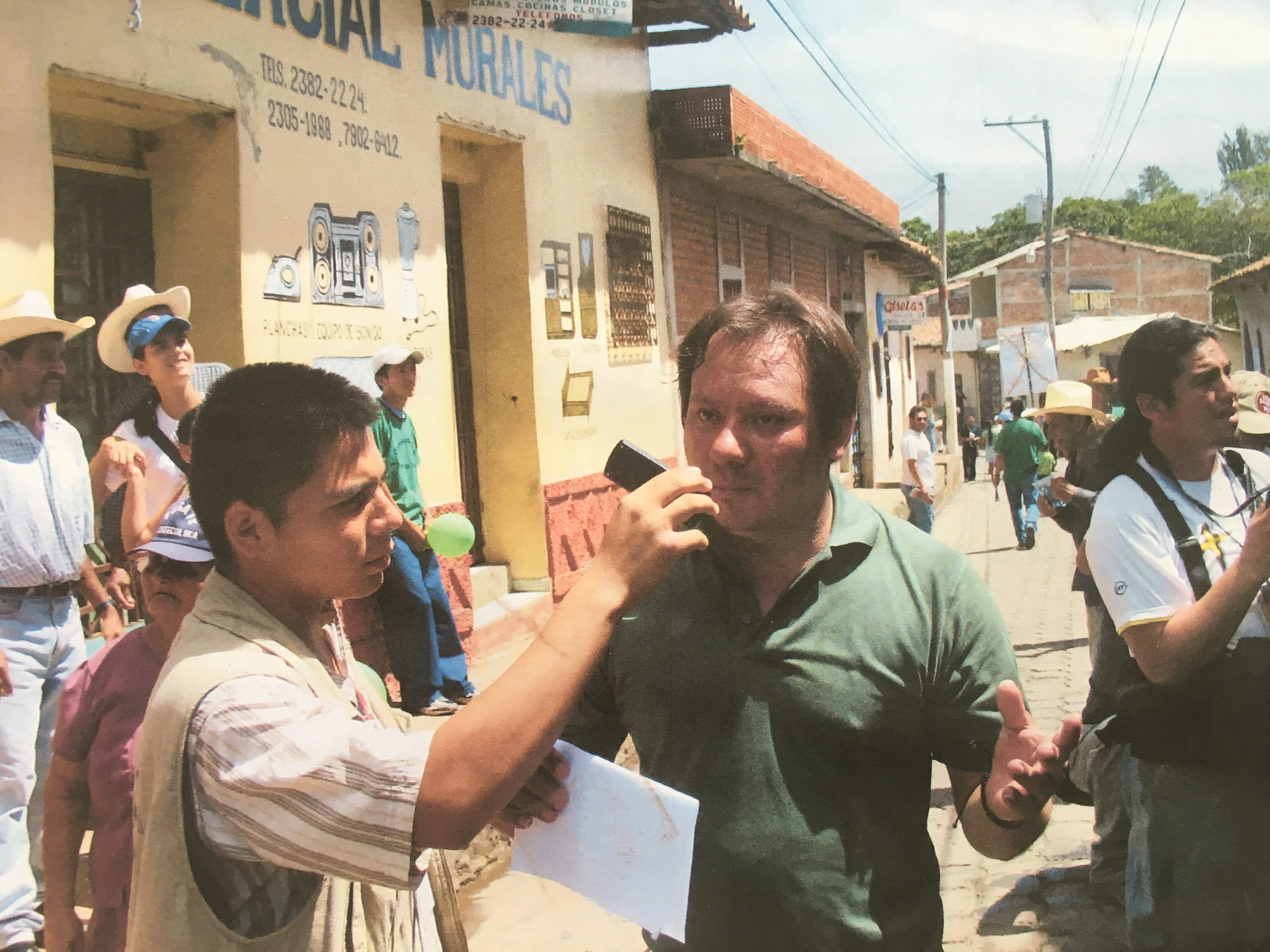

A Radio Victoria journalist interviews Marcelo Rivera

Local law-enforcement officers said that Marcelo had been drinking with members of a gang when a fight broke out, and that his murder was the result of ‘common delinquency’. In September 2010, three gang members were convicted of killing Marcelo, and three more sentenced for covering up the case.

Given the details of Marcelo’s activism and the context in which he was murdered, this was an unsatisfactory legal decision. Many believe his murder was, in reality, an example of a phenomenon that is frequently encountered in El Salvador, where gangs are hired as hitmen to carry out the dirty work of powerful people linked to organized crime. ‘It wasn’t just a small group,’ said Beltrán. ‘This was a large group of armed people who had military experience. The shells left behind where they shot Ramiro [one of the other victims] were from an M16 rifle. Those are military-issue only.’ While these details fuel speculation, there have been few answers. But it seems clear that the violence was intended to advance pro-mining interests. ‘It’s not our job to investigate,’ says Miguel Ángel.

A decade later, investigations have failed to reveal who masterminded Marcelo’s murder. Pacific Rim has repeatedly denied involvement in his murder and the killings of other activists.

Beltrán said that the murder was intended to send a message: ‘“If we’re capable of doing this to Marcelo, we can do anything to you.” Emotionally, it hit us. Confronting the mining company meant confronting economic powers. But for us to be silent would have been inconsistent with Marcelo’s work.’

In October 2016, Pacific Rim – now OceanaGold – lost its case at the World Bank’s ICSID tribunal. And in 2017, El Salvador became the first country in the world to impose a ban on all metal mining.

14 August 2005

Esteli, Nicaragua

Adolfo Olivas

2 March 2016

Honduras

Berta Cáceres

6 November 2011

Penonomé, Panama

Darío Fernández

15 May 2022

Santander de Quilichao, Colombia

Édgar Quintero

7 December 2018

Cauca, Colombia

Edwin Dagua

9 August 2023

Quito, Ecuador

Fernando Villavicencio

15 May 2017

Culiacán, Mexico

Javier Valdez

18 October 2016

Tocoa, Honduras

José Ángel Flores

9 May 2018

San Luis Jilotepeque, Guatemala

Luis Marroquín

30 March 2020

Papantla, Veracruz, Mexico

María Elena Ferral Hernández

14 March 2018

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Marielle Franco

15 March 2016

Honduras

Nelson García

16 January 2009

Valencia, Venezuela

Orel Sambrano

13 October 2017

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Yuniol Ramírez

31 March 2020

Zutiwa, State of Maranhão, Brazil

Zezico Guajajara