15 May 2017

Culiacán, Mexico

Javier Valdez

Profession

Media

Motive

Exposure of illegal activity

Adolfo Olivas

Ahmed Divela

Amit Jethwa

Artan Cuku

Babita Deokaran

Bayo Ohu

Berta Cáceres

Bhupendra Veera

Bill Kayong

Boris Nemtsov

Boško Buha

Chai Boonthonglek

Charl Kinnear

Chut Wutty

Chynybek Aliev

Cihan Hayirsevener

Daphne Caruana Galizia

Darío Fernández

Derk Wiersum

Deyda Hydara

Édgar Quintero

Edmore Ndou

Edwin Dagua

Federico Del Prete

Fernando Villavicencio

Gezahegn Gebremeskel

Gilles Cistac

Habibur Mondal

Igor Alexandrov

Jacob Juma

Ján Kuciak

Javier Valdez

Joannah Stutchbury

José Ángel Flores

Jules Koum Koum

Kem Ley

Luis Marroquín

Mahamudo Amurane

Marcelo Rivera

María Elena Ferral Hernández

Marielle Franco

Milan Pantić

Milan Vukelić

Muhammad Khan

Nelson García

Nihal Perera

Oliver Ivanović

Orel Sambrano

Perween Rahman

Peter R. de Vries

Rajendra Singh

Salim Kancil

Sandeep Sharma

Sikhosiphi Radebe

Slaviša Krunić

Soe Moe Tun

Victor Mabunda

Virgil Săhleanu

Wayne Lotter

Yuniol Ramírez

Zezico Guajajara

15 May 2017

Culiacán, Mexico

Profession

Media

Motive

Exposure of illegal activity

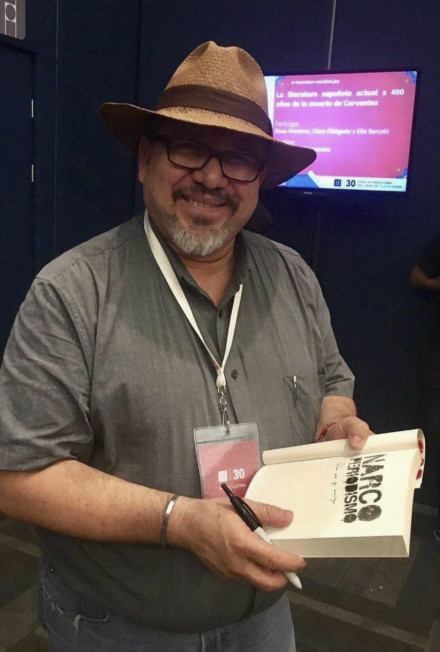

Javier Valdez was a sociologist and writer who loved music, literature, politics, social struggle and poetry. For him, being a journalist meant fighting for social justice, even if it was a solitary struggle. He led a small newsroom that published a weekly newspaper, Ríodoce, which focused on drug-trafficking news and analysis.

His values shone through in the speech he gave on receiving the Committee to Protect Journalists’ international press freedom award in 2011: ‘This award is like a ray of light from the other side of the storm … At Ríodoce we have experienced a macabre solitude because none of what we publish has an echo or is followed up, and that makes us feel more vulnerable … This award makes me feel that I have a safe haven, a place where I can feel less lonely.’

Valdez was murdered on 15 May 2017. He died from multiple gunshot wounds. His body lay on the hot asphalt, under the scorching sun, his hat beside him. He was 50 years old.

According to the crime scene reconstruction carried out by forensic experts from the attorney general’s office and the Special Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes against Freedom of Expression (FEADLE in Spanish), Valdez was driving his car when his killers cut in front of him. The incident happened in the city centre a short distance away from the Ríodoce office. Two of the killers ordered Valdez out of his car and shot him. One of them then took his car; the other two fled in their own vehicle.

A few months before his murder, the city of Culiacán faced a grim scenario. The Sinaloa Cartel, one of the most powerful transnational drug networks in the world, was being ripped apart by an internal power struggle. Culiacán, capital of the state of Sinaloa, in north-west Mexico, was the cartel’s centre of operations, and the city where its turf wars took place. The conflict was between two factions of the cartel – one led by Iván Archivaldo and Alfredo Guzmán Salazar, both sons of notorious drug lord Joaquín Guzmán Loera, known by his street name, El Chapo, who, some two years later, in February 2019, was found guilty in a US court of operating a violent transnational drug network and sentenced to life imprisonment. The other cartel faction was led by Dámaso López Núñez, a former police officer, and his son Dámaso López Serrano.

Javier Valdez and Ríodoce’s newsroom decided to cover the conflict. ‘We thought we were immune to the violence,’ said Ríodoce’s director, Ismael Bojórquez. Somehow, they had always managed to report on drug-related conflict without losing lives. After Valdez’s death, Bojórquez took part in public forums and demonstrations. He said he felt it was necessary to speak out to demand justice in a country where 99.6 per cent of attacks on journalists go unpunished.

Valdez’s death elicited an unprecedented reaction from the journalistic community and others. There wasn’t a single media outlet that didn’t talk about his case or uphold it as an example of Mexico’s law-enforcement and security crisis. Before his death, and more so afterwards, Valdez was well known. He had helped journalists and academics better understand the origins of drug trafficking, reporting from Sinaloa, the province dubbed the birthplace of Mexican drug cartels. He was known for his sensitive journalistic reporting and his books, for giving the victims of violence a voice, for his resilience and for his tenacity as a journalist in the midst of a drugs war.

Once asked what it was like to cover security issues in Sinaloa, he said that he reported ‘with his hands on his ass’, meaning he clearly feared for his life. ‘In Culiacán, living is dangerous,’ he said, ‘and working as a journalist means treading an invisible line drawn by the bad guys from both the drug cartels and the government – a sharp floor covered with explosives.’

The investigation indicates that Valdez was murdered because of his work as a journalist, and points the finger of blame at the cell led by Dámaso López Núñez. Before he was extradited, Dámaso admitted that the cell that killed Valdez worked for him but claimed he was in prison at the time and that he had not ordered the murder.

Bojórquez explained how Valdez had written a series of articles before he was murdered: ‘Javier interviewed Dámaso in February, and that caused friction with rival groups and a tense atmosphere in the newsroom.’ La Jornada journalist Miroslava Breach was killed in March, and it appears, said Bojórquez, that ‘someone within Dámaso’s organization ordered Javier’s murder as a result of the information published by Ríodoce, and possibly La Jornada, too’.

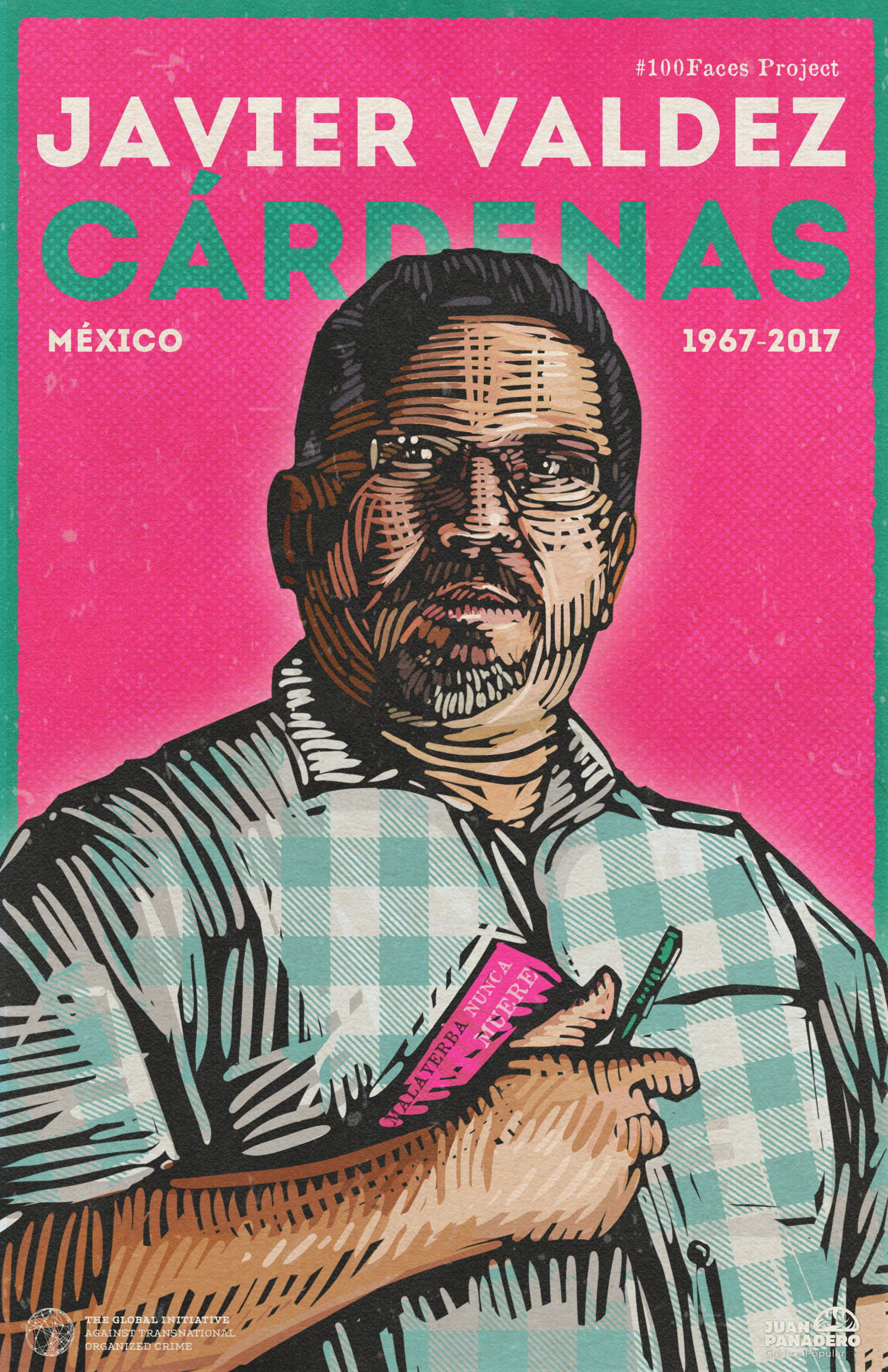

After the assassination, a group of local artists used walls in central Culiacán to honour the journalist. Illustration by El Dante

On 1 May 2017, Ríodoce had published a story based on articles written by Javier Valdez, which could have angered Dámaso senior and junior, according to Bojórquez. In one piece, published about a year earlier, Valdez made acid remarks about Dámaso Junior’s behaviour: ‘Dámaso López Serrano has been described as a smooth talker but a poor businessman. He only enjoys the spoils of the business run by his father, or the business his father used to run. [He] is a drug trafficker who pays musicians to compose corridos [ballads] for him and who struts around with his firearms during weekends …’

After the murder, the authorities identified three killers: Heriberto Barraza Picos, known as El Koala, Juan Francisco Picos Barrueto (street name El Quillo) and Luis Idelfonso Sánchez Romero (El Diablo). The first two were arrested; the third was killed in September 2017.

‘The problem is not the focus of the investigation. The question is whether the FEADLE will be able to prove to a judge, beyond reasonable doubt, that El Koala and El Quillo ordered Javier’s murder,’ said Bojórquez. ‘I’m sure they did it, but the judge needs to be sure too.’

On 26 July 2017, Dámaso López Serrano turned himself in to the police at the Calexico border crossing in California, where a warrant for his arrest had been issued. The authorities have yet to release official information about the individuals behind Valdez’s murder. The case is still under investigation.

Valdez’s widow, Griselda Triana, whose relationship with her late husband went back to the days before he became a best-selling author, and before he founded Ríodoce, said, ‘We lose precious people who use their words to lay bare the truth about a rotten society – with useless institutions that treat the victims with contempt … he was snatched away from us,’ she said.

Triana believes that the arrested men carried out the hit on Valdez, but fears those who ordered the assassination are still at large.

September 2022 update

The two identified perpetrators were later sentenced to prison, accused of participating in Valdez’s murder. In February 2020, El Koala was sentenced to 14 years and eight months. In June 2021, a federal judge in Culiacán sentenced El Quillo to 32 years and three months. According to the prosecution, El Quillo committed the murder by orders of Dámaso López Serrano.

López Serrano had been held in custody on drug trafficking charges in the United States since 2017. However, after serving a 72-month sentence, he was released in September 2022. Griselda Triana fears he will not face criminal charges for Valdez’s murder and called for the Mexican government to expedite his extradition from the United States.

14 August 2005

Esteli, Nicaragua

Adolfo Olivas

2 March 2016

Honduras

Berta Cáceres

6 November 2011

Penonomé, Panama

Darío Fernández

15 May 2022

Santander de Quilichao, Colombia

Édgar Quintero

7 December 2018

Cauca, Colombia

Edwin Dagua

9 August 2023

Quito, Ecuador

Fernando Villavicencio

18 October 2016

Tocoa, Honduras

José Ángel Flores

9 May 2018

San Luis Jilotepeque, Guatemala

Luis Marroquín

9 July 2009

San Isidro, El Salvador

Marcelo Rivera

30 March 2020

Papantla, Veracruz, Mexico

María Elena Ferral Hernández

14 March 2018

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Marielle Franco

15 March 2016

Honduras

Nelson García

16 January 2009

Valencia, Venezuela

Orel Sambrano

13 October 2017

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Yuniol Ramírez

31 March 2020

Zutiwa, State of Maranhão, Brazil

Zezico Guajajara