26 April 2012

Koh Kong, Cambodia

Chut Wutty

Profession

Community

Motive

Environmental and indigenous activism

Exposure of illegal activity

Adolfo Olivas

Ahmed Divela

Amit Jethwa

Artan Cuku

Babita Deokaran

Bayo Ohu

Berta Cáceres

Bhupendra Veera

Bill Kayong

Boris Nemtsov

Boško Buha

Chai Boonthonglek

Charl Kinnear

Chut Wutty

Chynybek Aliev

Cihan Hayirsevener

Daphne Caruana Galizia

Darío Fernández

Derk Wiersum

Deyda Hydara

Édgar Quintero

Edmore Ndou

Edwin Dagua

Federico Del Prete

Fernando Villavicencio

Gezahegn Gebremeskel

Gilles Cistac

Habibur Mondal

Igor Alexandrov

Jacob Juma

Ján Kuciak

Javier Valdez

Joannah Stutchbury

José Ángel Flores

Jules Koum Koum

Kem Ley

Luis Marroquín

Mahamudo Amurane

Marcelo Rivera

María Elena Ferral Hernández

Marielle Franco

Milan Pantić

Milan Vukelić

Muhammad Khan

Nelson García

Nihal Perera

Oliver Ivanović

Orel Sambrano

Perween Rahman

Peter R. de Vries

Rajendra Singh

Salim Kancil

Sandeep Sharma

Sikhosiphi Radebe

Slaviša Krunić

Soe Moe Tun

Victor Mabunda

Virgil Săhleanu

Wayne Lotter

Yuniol Ramírez

Zezico Guajajara

26 April 2012

Koh Kong, Cambodia

Profession

Community

Motive

Environmental and indigenous activism

Exposure of illegal activity

When journalist Olesia Plokhii and her Cambodian colleague went on a reporting trip to investigate illegal logging in Cambodia’s east, they never imagined the turn it would take. ‘It was a horrific moment, you know, everything in your stomach drops,’ said Plokhii. ‘I looked over my shoulder and in the distance behind us we saw two motorcycles. Three soldiers and military police were coming on two bikes. They had AK-47s strapped to their backs.’

Environmental activist Chut Wutty had taken the two reporters from the national newspaper Cambodia Daily to a site belonging to the Timbergreen Company in Koh Kong, where he believed illegal logging was taking place in the rainforest. Wutty would not survive the day.

Wutty had been a Russian-trained Cambodian military officer before he turned to environmental protectionism at the beginning of the 2000s. When he saw that natural resources were being destroyed by corrupt officials and rich businessmen, he began to work with NGOs, such as Global Witness and Conservation International, before starting his own organization aimed at protecting Cambodia’s already depleted forests from illegal logging. In his work, Wutty had led local communities to patrol forests and burn any illegally logged wood they found.

His military background came in useful, said Plokhii. ‘He had a lot of institutional knowledge. He also had an emotional knowledge. He was tuned in, he knew people, he knew the answers. He knew etiquette and he was passionate, and he was willing to die for what he did.’

Marcus Hardtke, an independent environmentalist in Cambodia who worked closely with Wutty for about a decade, said that illegal logging is made possible by corruption at the highest levels of the Cambodian government. According to Hardtke, local governments tolerate illegal logging activities because they are paid off by both small-time and big-scale loggers. This corruption reaches high-ranking government officials, he said.

Hardtke described illegal logging as a ‘textbook’ example of organized crime. ‘It operates outside the law,’ he said. He explained it as being a hierarchical system, in which each person must pay a sum to the next person above them in the chain of power. This might be a formal superior, he said, or someone who holds more authority because of their position in the government, connections to authorities, or wealth. Attempting to interfere in that chain is a dangerous game, Hardtke said. ‘It elicits threats and, occasionally, killings.’

According to Plokhii, Wutty believed that rich businessmen and government officials should not profit from destroying the livelihoods of people dependent on forests. This belief would eventually cost him his life. Being a thorn in the sides of many well-connected businessmen, Wutty regularly faced threats from illegal loggers and authorities.

On the afternoon of his death, Wutty’s old car wouldn’t start when he tried to drive himself and the two reporters to safety. By the time they had managed to shortcut the wires and start the car, it was too late. ‘Right when I was about to open the driver-side door, I heard a shot towards the car,’ Plokhii said. Wutty was dead.

Plokhii and her colleague first fled into the forest, but then decided to turn back, as their chances of surviving in the jungle were even slimmer. By the time they returned, one of the military police officers, In Rattana, was also dead.

In October 2012, a court found Timbergreen’s chief security guard, Rann Borath, guilty of ‘unintentional homicide’ for the death of Rattana and handed him a two-year jail sentence, three-quarters of which was suspended. Prosecutors had argued that Rattana had in fact shot Wutty. They said Borath had then tried to take Rattana’s rifle and accidentally pulled the trigger, killing the military officer. ‘It was a cover-up,’ Plokhii said.

Borath was released shortly after the trial. Human-rights organizations continue to call for a thorough and independent investigation into the murder. The government itself offered a variety of explanations, including that Rattana had shot himself out of remorse, that he had shot himself twice by accident, and even that Wutty had shot him. Human-rights organizations and observers have deemed all of those explanations implausible; many questions remain.

Wutty’s son, Cheuy Oudom Reaksmey, is one of those still searching for justice. His childhood was shaped by his father’s environmental activism. Reaksmey described how Wutty would barely sleep at home and would come to their house on the outskirts of Phnom Penh perhaps only twice a month. The rest of the time he would sleep in the countryside or in his office in the capital.

Chut Wutty and his son Cheuy Oudom Reaksmey (third and fourth from left) on a field trip

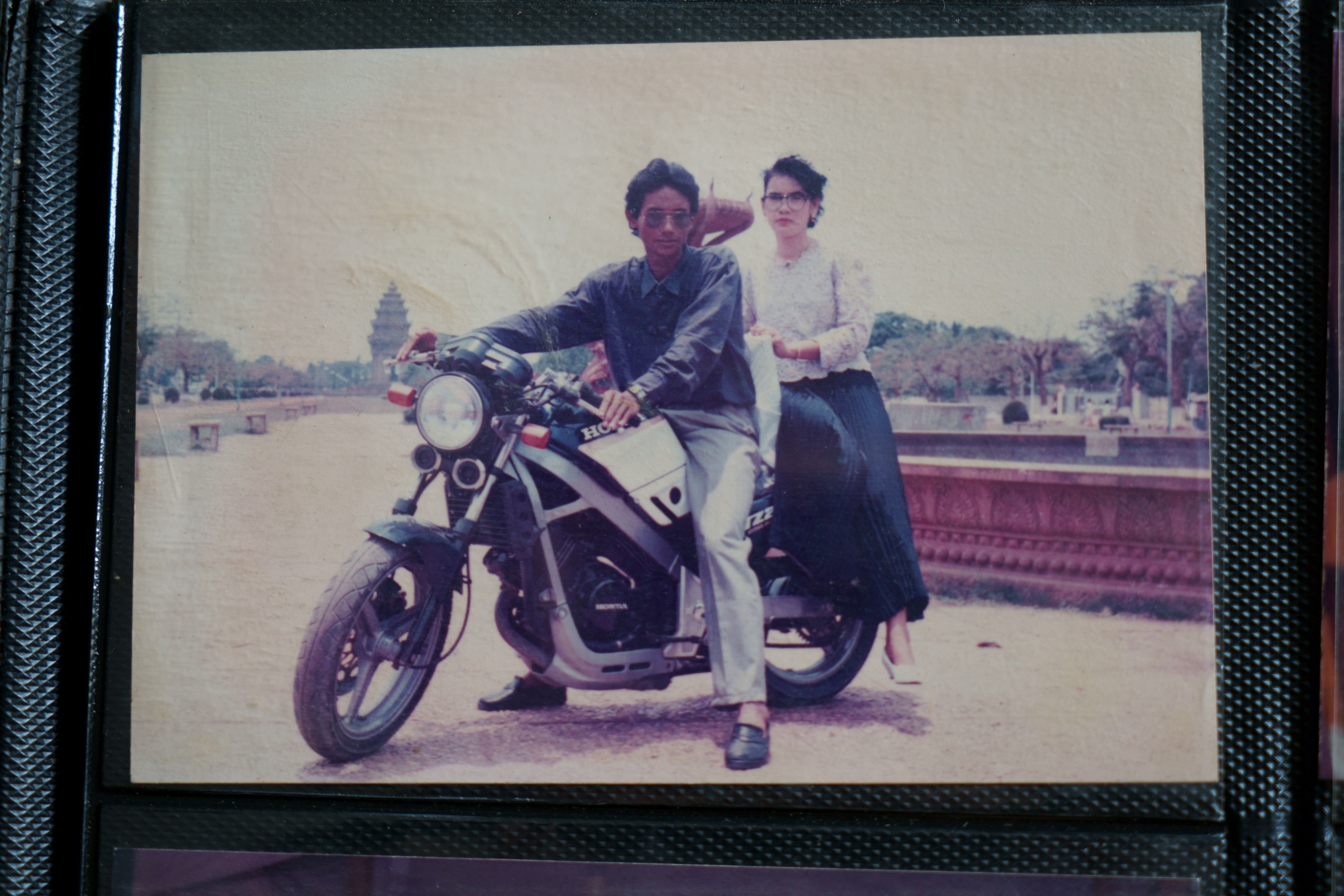

Wutty and his wife in front of Independence Monument, Phnom Penh

Wutty's son at a memorial at the scene of the shooting

Now 27, Reaksmey has long followed in his father’s footsteps. In 2016, he took over the presidency of Wutty’s NGO, Natural Resource Protection Group, but his engagement in environmental causes dates back to his childhood. As a teenager, he would often accompany his father on trips while he was patrolling the forests. They would visit communities and discuss strategies for countering illegal logging.

This brought Reaksmey close to the risks the work entailed.

‘I used to tell him to stop because one day he would die. But he wanted to die, because he wanted to die in honour,’ Reaksmey said. ‘It was hard for me as a child to tell him what to do. His personality was like a soldier; he forged ahead.’

Yet, despite being aware of the risks, Reaksmey didn’t actually believe that his father would be assassinated; he was more worried about him being arrested or beaten up.

On several previous occasions, Reaksmey had been relayed rumours that his father had died – all proven wrong. So when he received the phone call on 26 April 2012, he at first took it for yet another unsubstantiated rumour. ‘At 10 a.m. [my father] had called me and told me that he would be travelling back to Phnom Penh,’ Reaksmey revealed. Just two hours later, Wutty was shot.

‘I could not believe it until I saw his body,’ said Reaksmey. ‘It is difficult to accept that, because we used to have a father and now we don’t.’

20 July 2010

Gandhinagar, India

Amit Jethwa

15 October 2016

Mumbai, India

Bhupendra Veera

21 June 2016

Sarawak, Malaysia

Bill Kayong

11 February 2015

Klong Sai Pattana, Thailand

Chai Boonthonglek

5 May 2004

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Chynybek Aliev

20 August 2000

Dhaka, Bangladesh

Habibur Mondal

10 July 2016

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Kem Ley

16 October 2018

Haripur, Pakistan

Muhammad Khan

5 July 2013

Deraniyagala, Sri Lanka

Nihal Perera

13 March 2013

Karachi, Pakistan

Perween Rahman

19 June 2018

India

Rajendra Singh

26 September 2015

Selok Awar-Awar, East Java, Indonesia

Salim Kancil

24 March 2018

Bhind, Madhya Pradesh, India

Sandeep Sharma

13 December 2016

Monywa, Myanmar

Soe Moe Tun